The first two sentences delivered by the U.S. representative at the 3rd session of FfD4 Preparatory Committee (3rd PrepCom) last week were already tough ones: “At the outset, I underscore that the United States is currently evaluating its membership and participation in all international organisations and processes. Thus, we are reserving on the whole draft at this time.” With this statement, the elephant in the room – the role of the new U.S. administration in the FfD negotiations – was finally addressed. And what the elephant said was unsettling: It questioned the U.S. participation altogether. (mehr …)

Schlagwort: WTO

-

Investment Facilitation for Development – What’s at stake at the 13th Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization?

The current debate on the Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement could be very consequential for the World Trade Organization (WTO) although it is not part of the official calendar of next week’s 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) in Abu Dhabi. (mehr …)

-

Biden’s Geo-Economics Forces De-Globalization

Under US President Joe Biden America continues to threaten the rules-based world economic order and is pushing the trend towards de-globalization. Although the new Biden administration rhetorically seeks more „values“ and the „community of democracies,“ the United States is still at its core seeking to protect its national interests with all its economic and military power.

-

Globalisation is on the ventilator – Long live globalism!

Source: https://www.wallpaperflare.com/old-world-map-jigsaw-puzzle-fun-game-entertainment-the-board-wallpaper-zvmre Globalisation Unmasked

The world is grappling with a deadly pandemic unleashed on the planet by the Corona Virus (SARS-CoV-2/ HCoV-19). In its wake, the votaries of globalisation who have been espousing the cause of a borderless world of business with seamless flow of international trade, capital and even human resources across the world seem to be stung by a creepy realization whether the paeans sung by them were all worth the effort. More than the social and cultural aspects of globalisation, its economic manifestation in the form of product market integration with concomitant cross-border value chains has been credited with having contributed richly to the growth of the global and national economies. Today, more than half the world has locked down their economic, social, political and cultural activities to arrest the spread of the corona virus that has already infected nearly eight million patients world-wide and claimed over four hundred thousand lives as on the 15 June, 2020. (mehr …)

-

A quid pro quo to save the WTO’s Appellate Body

Emerging countries such as Brazil, Mexico, India, China, Korea, Thailand, Indonesia and to a lesser degree, Vietnam and Turkey have actively and successfully invoked the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system (DSS) to defend their commercial interests. With increased participation in world trade, their stake in an effective compulsory and binding mechanism for resolving conflicts becomes even more relevant to enforce the rules and uphold foreign market access. In a global context of great trade frictions, the preservation of such a mechanism, including the quasi-automatic adoption of reports under the reversed-consensus rule, which means that actions can go ahead unless there is a consensus of WTO members not to do so, becomes a first-order priority. The mechanism could be perfected further to level power imbalances. But the task at hand now is more fundamental: to unblock the impasse of the Appellate Body (AB). While this crisis is not of the emerging countries’ making, they may hold a key to unlock it: they could give up their prerogative to “special and differential treatment” (SDT) in future trade negotiations in return for a commitment by the United States to restore the AB.

Emerging countries such as Brazil, Mexico, India, China, Korea, Thailand, Indonesia and to a lesser degree, Vietnam and Turkey have actively and successfully invoked the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system (DSS) to defend their commercial interests. With increased participation in world trade, their stake in an effective compulsory and binding mechanism for resolving conflicts becomes even more relevant to enforce the rules and uphold foreign market access. In a global context of great trade frictions, the preservation of such a mechanism, including the quasi-automatic adoption of reports under the reversed-consensus rule, which means that actions can go ahead unless there is a consensus of WTO members not to do so, becomes a first-order priority. The mechanism could be perfected further to level power imbalances. But the task at hand now is more fundamental: to unblock the impasse of the Appellate Body (AB). While this crisis is not of the emerging countries’ making, they may hold a key to unlock it: they could give up their prerogative to “special and differential treatment” (SDT) in future trade negotiations in return for a commitment by the United States to restore the AB.The WTO dispute settlement system has worked for the larger developing economies

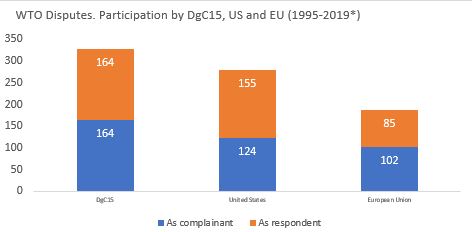

Figure 1. Source: Author, based on WTO, https://data.wto.org Since 2000, developing countries’ share in world merchandise trade has increased from 34.7 percent to 47.8 percent in 2017 driven mostly by China, which accounts for about a third of that growth, and by 14 other developing economies: Korea, Hong Kong, Mexico, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, India, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa. With 35.5 percent of global merchandise exports in 2017, up from 22.7 percent in 2000, these economies account for some three-quarters of all developing countries’ exports of goods.

With such a remarkable trade performance comes increased potential for trade conflict. It is thus no surprise that with a cumulative participation as parties in a total of 328 cases during the 1995-2019 period, the 15 larger developing countries (DgC15) have actually become the main users of the DSS (see figure 1).

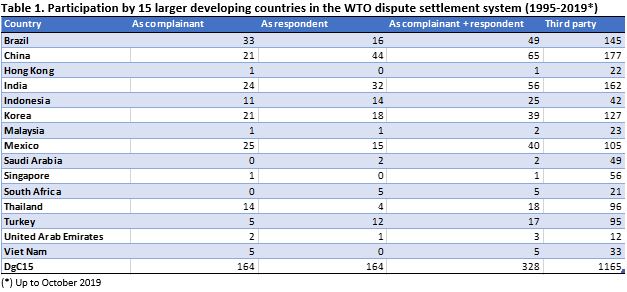

Among the DgC15, China, India, Brazil, Mexico and Korea have participated in a total of 249 cases as complainants and respondents, which accounts for about three-quarters of this group’s participation (see table 1). They are also the most active third parties. Indonesia, Thailand and Turkey, with 25, 18 and 17 cases each, emerge as important users of the system, though not as active as the first group. The rest of the countries have participated in a limited number of disputes, ranging from 1 to 5.

Table 1. Source: WTO The system has worked well for the DgC15. As complainants, they have won, partially won or reached a mutually agreed solution in 48 percent of cases (excluding ongoing cases), whereas as respondents the comparable figure is 25 percent. This is in line with the view that there is a process of self-selection of disputes, with countries normally activating the system to pursue cases they consider potential winners. In both cases, some 40 percent of conflicts have been terminated, withdrawn or dropped for unknown reasons. The “losing” record is higher when these countries participate as respondents, with some 35 percent of cases lost, than when they initiate a case, where some 13.5 percent of cases are lost. Even when a respondent “loses” a case in the legal sense it most frequently “wins” in economic terms by defeating domestic protectionist interests and restoring its own commitment to non-discrimination and open markets.

A deal to restore the Appellate Body

In negotiations, expanding the scope of the discussion sometimes helps to reach a bargain. In this case, another source of US frustration with the WTO is the perception that larger developing countries are exploiting the multilateral trading system unfairly because of advantages conferred to them under the SDT they may claim in negotiations. While the content of SDT is determined in the context of each WTO agreement, as a result of a negotiating process, typical SDT may include preferential market access or technical assistance, or it may allow exceptions to specific rules and liberalization commitments. The flexibilities accruing to developing country status are useful mostly for smaller and poorer countries, which may need them to implement complex agreements and to prepare to leverage the opportunities of international trade. But the evidence is mixed on the overall effectiveness of “special and differential” benefits. Lack of reciprocal engagement in negotiations has resulted in continued constraints for export sectors where developing countries typically possess comparative advantage, like agriculture or apparel. And by sometimes exempting themselves from reciprocal commitments, developing countries have missed opportunities to foster domestic reforms to support integration into global markets. Thus while the benefits accrued under the SDT are at best mixed, the loss of the WTO compulsory third-party adjudication regime is significant and real.

A quid pro quo, where the larger developing countries proactively propose to drop their request for SDT in ongoing and future negotiations in exchange for the US agreeing to the nomination of AB members could be the starting point of a bargain to preserve and improve the appeals procedure. Building on the decisions of Brazil and Korea to forego SDT, a broader group of emerging economies could come together to craft such a deal. Lifting the blockage of the AB nominations could pave the way for reasserting its role in the system.

But this bargain cannot work without the US engagement. It would remain to be seen if in the face of a deal, the United States will be ready to negotiate.