The current debate on the Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement could be very consequential for the World Trade Organization (WTO) although it is not part of the official calendar of next week’s 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) in Abu Dhabi. A group of WTO Members have launched discussions on a plurilateral agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development at the 11th Ministerial Conference in 2017. These discussions have turned into actual negotiations from September 2020 onwards and in July 2023, around two thirds of the WTO’s Memberships concluded text-based negotiations. At MC13, Members aim at finalising the negotiations and integrating the plurilateral IFD Agreement into the WTO legal system. So what is at stake? Why is the IFD Agreement so controversial? And what do we know about its potential economic effects?

The controversy on the IFD Agreement

On the one hand, the plurilateral negotiations on the IFD Agreement have strong support among the WTO’s Membership. Generally, such plurilateral agreements are negotiated among sub-groups of Members and bind only signatories, with a possibility to create benefits also for non-signatories. The initial Ministerial Statement form 2017, launching structured discussion on investment facilitation for development, was signed by 70 Members. Today, more than 120 countries support the Agreement. What is more, many of those belong to the low and middle-income countries’ group. It is a good sign that such a large group of Members want to use the – supposedly crisis-ridden – WTO as a platform to promote domestic reforms to attract more investment for enhancing sustainable development.

Furthermore, the IFD Agreement addresses mainly procedural and technical issues faced by foreign (and domestic) investors. It is about making investment frameworks more transparent, efficient and predictable without interfering with host countries’ right to regulate. Moreover, the IFD Agreement includes a comprehensive section on special and differential treatment, which should ensure that developing and least-developed countries are actually able to implement its provisions. This Agreement comes close to what can be described as an “inclusive and development-friendly plurilateral” and may serve as a blueprint for subsequent agreements, also because it includes commitments to support sustainable investments and responsible business conduct.

On the other hand, a number of WTO Members are opposed to the inclusion of the IFD Agreement into the WTO’s rulebook. In view of the WTO’s consensus-based approach, all Members have to agree to adopt plurilateral agreements under Annex IV of the Marrakesh Agreement. Countries like India and South Africa have argued that the current plurilateral negotiations are not consistent with the WTO’s multilateral approach. Furthermore, critics argue that there exists no official mandate to launch investment-related negotiations in the WTO. While these legal matters are subject to debate, the bottom line is that the adoption of the IFD Agreement is a highly political problem and that a number of countries prefer to tackle the issues of the Doha Development Round first, above all agricultural trade, before launching negotiations on new topics such as investment facilitation.

In addition to these legal and political challenges, a number of critics question the benefits the IFD Agreement would bring to its signatories. They argue that its provisions could restrict policy space and could even be used in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) proceedings. Furthermore, some argue that countries can adopt investment facilitation measures “unilaterally”, i.e. without the reform pressure of a binding international agreement. Unfortunately, all too often that is the point where the policy debate on the value added of the IFD Agreement is stuck.

There are good principled arguments one can put forward in favour of the IFD Agreement but also against it. The issue is that we lack empirical research on a number of key questions: what is the current practice in terms of investment facilitation measures already adopted at country level, what additional reform pressure would the IFD Agreement bring, what is the potential economic benefit of the Agreement and what are the key barriers for developing countries to implement it? Current research, for example on the effects of traditional bilateral investment agreements, are of limited value due to the legal and institutional differences vis-à-vis the IFD Agreement.

The potential benefits of the IFD Agreement – let the data speak

In order to assess the value added of the IFD Agreement we need to comprehensively analyse economies’ investment frameworks. More precisely, what kind of investment facilitation measures have WTO Members already adopted at national level and which additional investment policy reforms would they have to undertake to implement the IFD Agreement? The Investment Facilitation Index (IFI) offers a new and unique data set for researchers, policy makers and investment practitioners. The IFI comprehensively conceptualises investment facilitation along six policy areas and 101 different measures, and documents their current adoption for 142 economies.

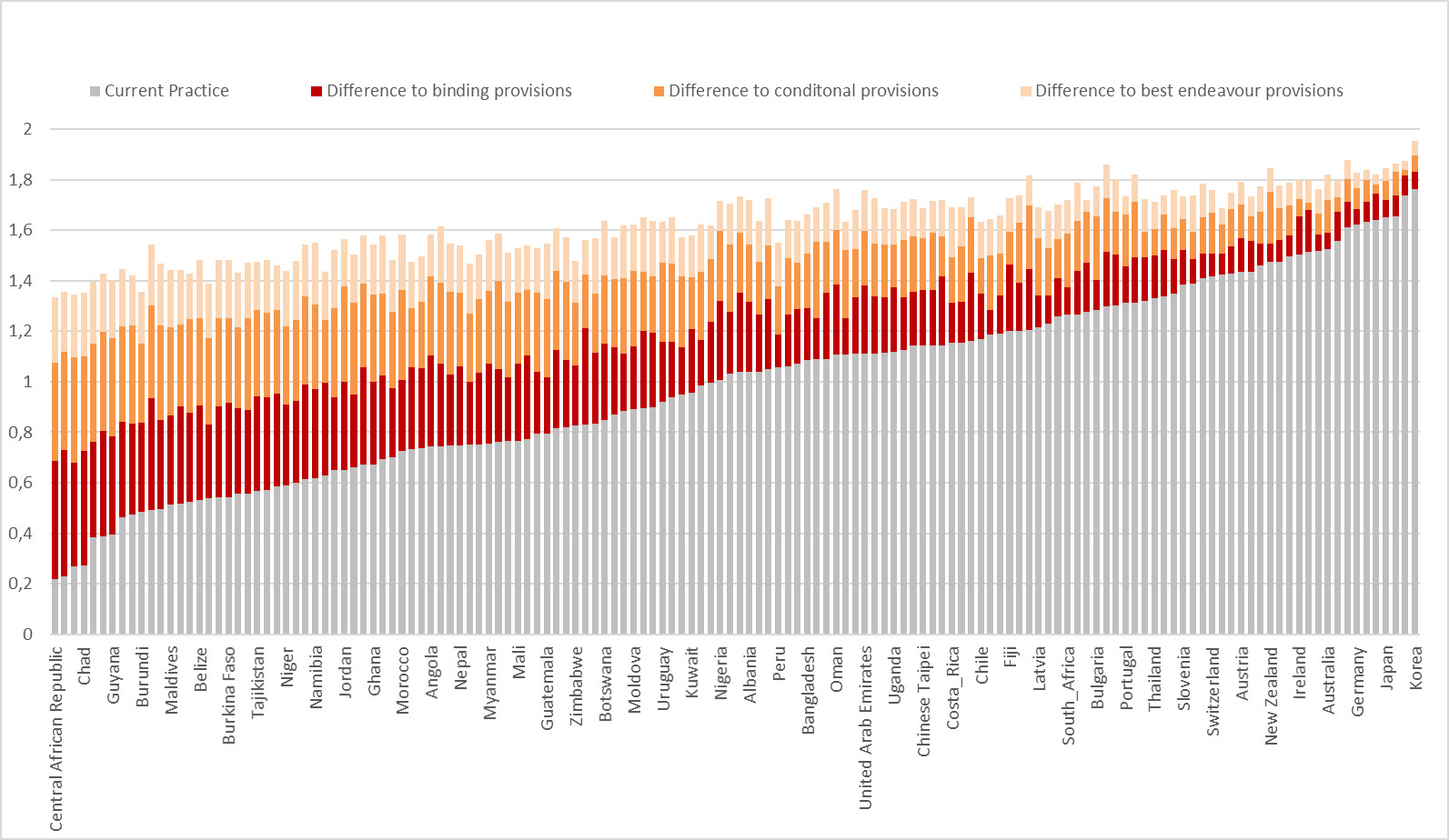

With the help of the IFI, we are able to quantify the advances countries have made in terms of reforming their investment frameworks and the challenges they are likely to face on the path to implementing the IFD Agreement. The IFI data illustrates significant differences in the current level of adoption of investment facilitation measures: High-income countries have already adopted over 62% of all analysed measures, while low-income countries have adopted only 29% (compared to the global average of 49%). The flipside of the current adoption level represents the reform gap economies face with respect to the IFD Agreement. In the figure below, we find the highest reform gaps in the countries with low levels of adoption and lower income on the left (e.g. Djibouti, Central African Republic, Chad, Liberia, Benin, Haiti, Eswatini). In contrast, lower reform gaps occur in high-income countries with higher adoption levels on the right of the figure.“. Such high-income countries as United Kingdom, Netherlands, Republic of Korea, Japan and the USA feature the lowest reform gaps among the 142 economies.

To reflect the legal language of the IFD text, we divide the overall reform gap into three parts:

- Red bars illustrate the reform gaps with respect to binding or “shall” provisions;

- Orange bars reflect conditional binding provisions (wording “shall, to the extent practicable”, “shall encourage”);

- And yellow bars point to non-binding or best endeavour provisions (wording “should”, “may”, “are encouraged”).

Figure: Investment Facilitation Index (IFI): Measuring IFD reform gaps

The figure clearly indicates that there is significant room for improvement, even for high-income countries. Implementing the different categories of the IFD provisions and going even beyond the Agreement’s text by incorporating additional measures would allow economies worldwide to improve their investment facilitation frameworks and reap the corresponding benefits.

Given all the illustrated reform gaps, what is actually the potential impact of the IFD Agreement? Our research, based on economic modelling, shows that the economic impacts of the IFD Agreement can be sizeable amounting to global welfare gains of 1.73%, which corresponds to $811 billion. While the implementation of binding commitments provides only limited gains (global welfare increase of 0.63%), a full implementation of conditional and best endeavor provisions is crucial for reaching the high benefits. In particular, implementation of both binding and conditional IFD provisions would double the worldwide benefits (1.29%), while adding best endeavour commitments would allow for the aforementioned global welfare gain of 1.73%.

Figure: Regional welfare impact (% equivalent variation)

Countries in the group of Friends of Investment Facilitation for Development (FIFD) as well as other low and middle-income countries would benefit most from the IFD Agreement and the assumed reduction of FDI barriers. The benefits increase for all if more countries sign up the Agreement. For example, the worldwide welfare goes up by 2.22% when India and the USA become part of the deal. For India this would mean a potential welfare gain of 1.98% - an increase by 2.5 times compared to the pure spillover effect of 0.79% when it remains an outsider. This example provides a strong incentive for non-participating developing countries to join the IFD Agreement, reform their investment frameworks and use the support structure contained in the section on special and differential treatment.

Jointly mastering the IFD implementation hurdles

In fact, to reap the suggested benefits of the IFD Agreement many developing countries will need additional technical assistance and capacity development support to adopt and implement investment facilitation measures. Such a technical assistance framework can be modelled in a similar way to the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which makes the implementation of certain trade facilitation measures by developing countries conditional on external support. Commitments to technical assistance and capacity development support are an integral part of the IFD Agreement and should be backed up by sufficient funding from high-income and upper-middle-income countries. Also, a closer cooperation between the WTO and other international organisations is essential for the undergoing needs assessment process and for future implementation of the IFD Agreement.

Despite all the legal and political debates, the IFD Agreement provides especially developing and least-developed WTO Members with a unique chance to boost their economies, to help achieving sustainable development goals through growing investment flows, even in challenging times of multiple crises and geopolitical tensions.

Schreibe einen Kommentar