In recent years, a growing number of G20 nation states have used various forms of summit diplomacy to enhance engagement with the African continent through regular high-level meetings. These have been operationalised through initiatives such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, India-Africa Forum Summit, Africa-EU Summit, the Korea-Africa Forum, the Turkey-Africa Partnership Summit, the United States-Africa Leaders Summit, and the Tokyo International Conference on African Development. Except for the summit with the EU, all of these initiatives are essentially putting together a single country with an entire continent. The partnerships span the parameters of both South-South and North-South cooperation, presenting opportunities for the African continent to diversify its international relations and cooperation.

In recent years, a growing number of G20 nation states have used various forms of summit diplomacy to enhance engagement with the African continent through regular high-level meetings. These have been operationalised through initiatives such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, India-Africa Forum Summit, Africa-EU Summit, the Korea-Africa Forum, the Turkey-Africa Partnership Summit, the United States-Africa Leaders Summit, and the Tokyo International Conference on African Development. Except for the summit with the EU, all of these initiatives are essentially putting together a single country with an entire continent. The partnerships span the parameters of both South-South and North-South cooperation, presenting opportunities for the African continent to diversify its international relations and cooperation.

The increased interest in Africa comes within the context of a continent that experienced an extended period of growth, with six to seven African countries repeatedly appearing in the list of the fastest growing economies in the world for an entire decade. With a young population projected to double to 2 billion by 2050, Africa was no longer only looking like the world’s problem, even though that narrative continues to be pervasive. It is increasingly obvious that Africa presents an opportunity for global powers; indeed the evidence suggests many opportunities to capitalize on the demographic dividend in Africa. This places a responsibility on African stakeholders to design strategies that will enhance the livelihoods of Africans and Africa’s place in the world.

The African continent needs to seize the initiative and shape those partnerships according to the individual, sub-regional, and collective interests of African stakeholders. Otherwise, it risks being mastered by its complex web of international partners instead. As the G20 seeks ways to engage the African continent, two important matters will have to be tackled in order to enhance African agency and institutionalise relation on equal terms. First, the issue of African representation in global summitry, and secondly, reducing the dependency on donors to finance Africa’s institutions such as the regional economic communities (RECs) and the African Union.

Who constitutes ‘Africa’ at global Summits?

The Kagame report on the imperative to reform the African Union, building on past initiatives such as the AU panel chaired by the late Professor Adebayo Adedeji, calls for the continent to rationalize its external partners, and to have a better distribution of labour between the various components of the AU system. The recommendations face the challenge of African nation states jealously guarding their sovereignty or looking to establish a sense of sovereignty in the first place. A key question will be who constitutes ‘Africa’ at the various summits with external powers.

The Kagame report recommends that ‘external parties should be invited to [AU] Summits on an exceptional basis and for a specific purpose, and that [p]artnership summits convened by external parties should be reviewed with a view to providing for an effective framework for African Union partnerships.’ It thus recommends that instead of all countries, Africa could be represented by:

- Chairperson of the African Union

- Previous Chairperson of the Union

- Incoming Chairperson of the Union

- Chairperson of the African Union Commission

- Chairperson of the Regional Economic Communities (RECs)

This would no doubt have an effect on the myriad partnership summits by individual G20 members and the shape and form that an institutionalised engagement between Africa and the G20 could possibly take. South Africa, like all other members of the G20 would thus be responsible for pursuing its national interests in the G20, which have a continental and global dynamic, whereas the official African representation would express the consolidated views from the continent. This would however need to form part of a broader G20 engagement with certain regions of the world, and not just be an Africa specific outreach. Indeed, the G20 already has EU representation through the EU Commission, and this would have to be seen in a similar light. While G20 decisions have an effect on much of the world’s population, there is no strong representation of least developed countries (LDCs) or regional bodies, and such an Africa outreach would have to be seen in the broader light of involving the rest of the world in G20 processes. It would thus be important to incorporate regional perspectives on the effects of G20 policies, especially on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and in terms of aligning it to Agenda 2063, the Africa-driven strategic framework for the socio-economic transformation of the continent over the next 50 years.

Financing Africa’s pan-African institutions

Also important to ensuring that African interests are taken on board is the ability of African stakeholders to finance their own regional cooperation, development agenda, and institutions such as the AU, which remains disproportionately financed by external donors, many of whom are members of the G20. The challenge is not to diversify its funders but to self-finance its institutions. Indeed the numbers tell a story that needs urgent addressing. According to the Kagame Report, ‘In 2014, the African Union’s budget was US$308 million, more than half of which was funded by donors. In 2015, it rose by 30 percent to US$393 million, 63 percent of which was funded by donors. In 2016, donors contributed 60 per cent of the US$417 million budget. In 2017, member states [were] expected to contribute 26 percent of the proposed US$439 million budget, while donors [were] expected to contribute the remaining 74 per cent.’

It further states that ‘The AU’s programmes are 97 per cent funded by donors. By December 2016, only 25 out of 54 member states had paid their assessment for the financial year 2016 in full. Fourteen member states paid more than half their contribution and 15 have not made any payment. This level of dependence on external partner funds raises a fundamental question: How can member states own the African Union if they do not set its agenda?’

An inability to fund its own institutions means that even if Africa’s engagement with external powers were to be institutionalised in a more coordinated manner, it would still not be on equal terms, as many of the G20 countries would in effect be dictating the agenda. The Kagame Report thus raises integral issues for Africa’s place in the world, namely domestic resource mobilization and representation. In the short to medium term, African countries will have to pay serious attention to the domestic mobilization of resources, which will also include addressing matters such as illicit financial flows.

Enhancing African agency in globalisation

The matter of self-financing the continent’s institutions is thus important to ensuring greater representation and the exercise of greater agency in Africa’s global partnerships in general, and with the G20 in particular.

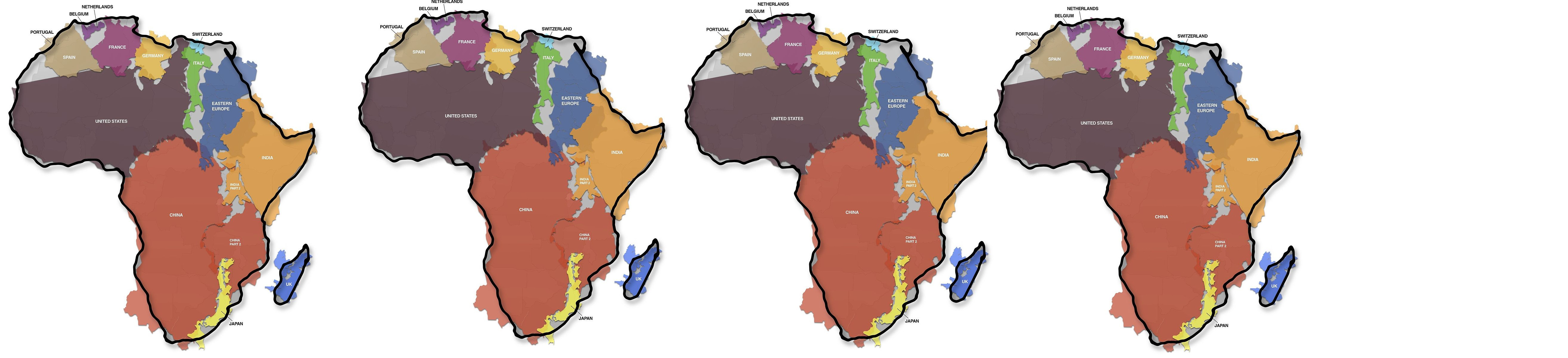

Africa is clearly not a monolithic actor, consisting of over 1 billion people with approximately 2000 languages and cultures, and a geographic space large enough to fit the United States, Western Europe, India, China, and Japan. It will thus be important for the vast array of state and non-state actors interacting with their interlocutors in the G20 countries to construct individual and sometimes collective strategies that engage with their counterparts in the global community.

If Africa is to move from being shaped by globalisation to shaping its evolution, then it must seriously address the matter of funding so that it advances its agency and provides greater representation for its people on the global stage. However, previous reform efforts must also be studied closely to understand why they were never fully implemented. While groups such as the T20, comprising think tanks from the G20 countries and the BRICS Academic Forum, which comprises think tanks and academic institutions from the BRICS countries, play important roles in fostering mutual understanding, they are not yet central to the ideas shaping the official summits. The challenge for think tanks is thus to use the platforms opening up to think tanks to build solid research communities amongst G20 and BRICS countries and institutions. Indeed think tanks must make use of the track two diplomacy and realise that global politics is no longer the domain of government-to-government relations alone.

Schreibe einen Kommentar