The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) – a US trade preference programme for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) – is back! At least for now. While the political signal of the extension is positive and surprising, the expected economic impact is rather negligible given its already limited effectiveness before the US break with the rules-based trading system. African policymakers should seize this moment to act: fast-track African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) implementation, deepen strategic EU partnerships, broaden export markets and product portfolios, and invest in moving up value chains—building a foundation for resilient trade that doesn’t depend on uncertain preferences and external policy shocks.

For more than two decades, the AGOA has been the cornerstone of the US development-oriented trade policy toward SSA. Together with the US Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) – a broader developing country tariff preference scheme, it long provided preferential market access combining trade and development objectives. Introduced in 2000, AGOA granted eligible African countries improved duty-free access to the US market.

On 3 February 2026, Donald Trump signed the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2026” (H.R. 7148) into law, extending AGOA until the end of 2026, with retroactive effect from its lapse end of last September. The expiry followed extended debate over the programme’s future, culminating in the bipartisan AGOA Renewal and Improvement Act of 2024, which sought a long-term extension and reform. However, President Trump’s “America First” agenda and erratic tariff changes stalled those efforts. Already earlier this year, the US House of Representatives passed a bipartisan bill for a simple three-year extension that reached the Senate but did not advance yet. Now the actual extension offers only a temporary reprieve without substantive reforms signalling a lack of real commitment to Africa’s long-term economic development.

Waning effectiveness

Even before this one-year extension, AGOA’s track record was mixed. While the programme had some success in boosting exports from specific countries and sectors, its overall effectiveness has been steadily declining. Utilisation rates – put simply, whether firms actually claim AGOA’s lower tariffs or instead export under standard Most Favoured Nation (MFN) rates – tell a sobering story: in 2008, over 80% of US imports from SSA countries benefited from AGOA and GSP preferences, but by 2021, this share had plummeted to just 24.7%.

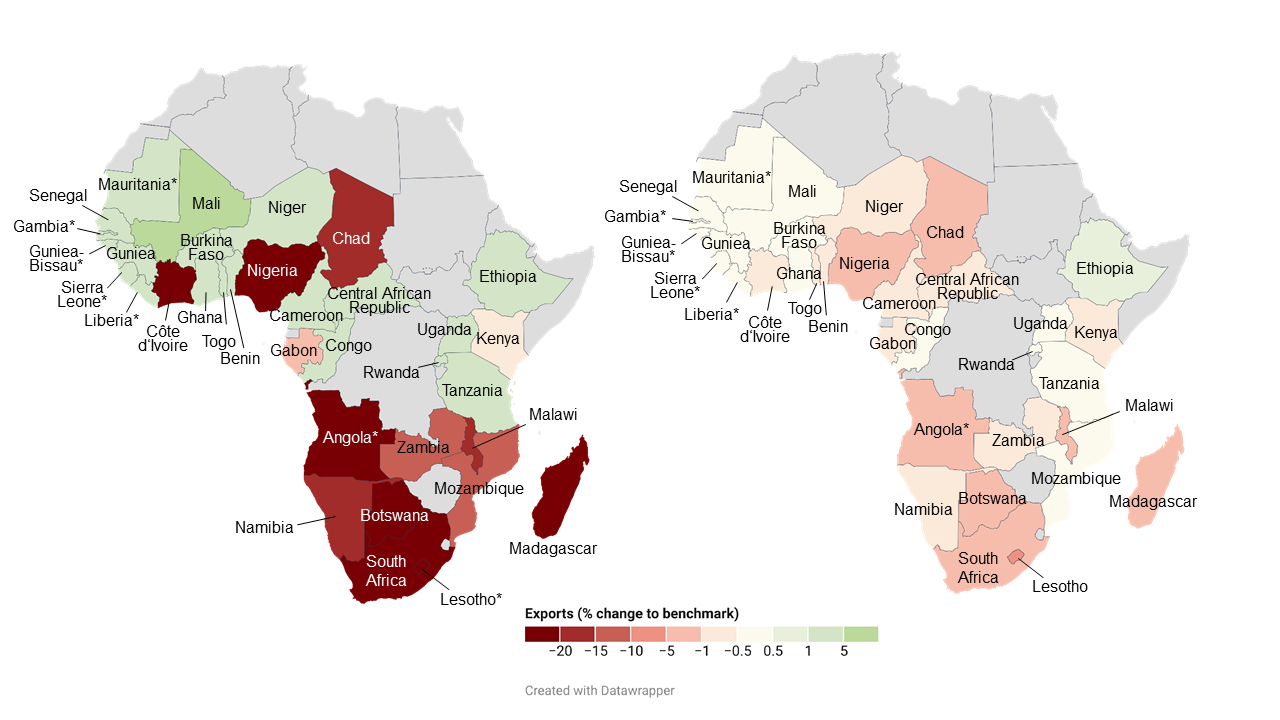

Simulation results underscore programme’s limited effectiveness: When simulating the shift from AGOA preferences to US MFN tariffs, we find that aggregate effects for AGOA-eligible countries are rather modest: bilateral exports to the US decline by 3.7%, while total exports fall by only 0.1%, with real GDP remaining almost unaffected. When we simulate the more drastic scenario of Trump-era „reciprocal tariffs“ on top of AGOA expiry, the picture still remains modest, yet more severe than the shift to US MFN rates, with total exports from AGOA-eligible countries declining by 1.1%. These muted aggregate effects largely reflect three factors: for most SSA economies, the US market matters less than the EU or China; meeting AGOA’s rules of origin can be costly; and the tariff advantage has been often limited because MFN rates are already relatively low. On top of that, uncertainty over continued country eligibility discourages firms from investing in compliance and reduces uptake of the programme.

Perpetual uncertainty

Uncertainty over AGOA eligibility and renewal has long undermined its effectiveness. Short renewal cycles discourage long-term investment, limit supply-chain integration, and weaken incentives for higher value-added activities — the very development outcomes AGOA was designed to promote. Since 2020, nine countries have lost eligibility, exposing exporters to the risk of abrupt preference removal. Complaints about the lack of transparency in eligibility review processes only amplify these risks for exporters and investors. Trade preferences work only if firms can reliably plan, making this one-year extension without clear path forward particularly problematic.

South Africa’s eligibility under the extension is still up for debate in Washington. Excluding South Africa would reduce the programme’s overall impact even further, since it is AGOA’s largest beneficiary in absolute terms: US imports from South Africa have surged by 270% over the past two decades. Simulations show that exclusion would hit key sectors hard: South African motor vehicle exports alone would fall 9.8% ($123 million) under MFN tariffs, further eroding the programme’s impact.

The (tariff) elephant in the room

The tariff environment has shifted in ways that further erode AGOA’s already limited preference margins, and this fundamentally changes the programme’s relevance for exporters. In 2017, the simple average US MFN tariff was already low at 3.3%, with less than a quarter of tariff lines above 5%. Since April 2025, the US has announced additional bilateral “reciprocal” tariffs on top of MFN rates illustrating a sharp departure from the WTO’s core principles of reciprocity and non-discrimination. Among AGOA-eligible countries, these surcharges currently range between 10% (e.g. in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo and others) and 30% for South Africa. AGOA only waives the significantly smaller MFN component, while leaving these new additional bilateral surcharges unchanged. This diminishes the preferential effect relative to the overall duty burden. Hence, it offers only a modest advantage vis-à-vis other developing countries still having to pay MFN tariffs.

In practice, these additional “reciprocal” tariffs are likely to bite hardest where AGOA should matter most: in poorer, more US-dependent economies with limited ability to absorb tariff shocks or re-route trade. Simulation evidence on the introduction of bilateral “reciprocal” tariffs (in addition to AGOA expiry) shows that countries highly dependent on specific exports to the US face significant losses: Lesotho’s total exports could decline by 5.9%, Madagascar’s by 3.3%, and both Chad and Botswana by 1.9% (see Figure). The sectoral impacts are even more severe. The wearing apparel sector, an important driver for employment in several SSA countries, would see bilateral exports to the US plummet by nearly half. For countries like Madagascar and Mauritius, apparel exports to the US would drop by almost 90%, wiping out total apparel exports by $128.5 million and $147 million. Such a trade shock could trigger significant negative effects on poverty in already fragile economies.

Figure: Export changes of AGOA-eligible countries to the US (left) and world (right) with “reciprocal” US tariffs

Notes: Countries marked in grey were not eligible for AGOA preferences in 2017. The only exception is Djibouti, which was AGOA-eligible in 2017, but is not separately covered for data availability reasons. * Indicates that a country is part of a “rest region” due to data restrictions.

Source: Britz, Olekseyuk and Vogel (2025).

Reform or irrelevance

An economically meaningful AGOA extension capable of unlocking its potential as a catalyst for African development requires comprehensive reforms. Key proposals from the stalled 2024 AGOA Renewal and Improvement Act offer a strong start:

- 16-year extension to 2041

- Biennial eligibility reviews instead of annual

- Granular enforcement options like product-specific suspensions or warnings instead of full termination

- Greater transparency in eligibility reporting

- Rules-of-origin modified to include North African AfCFTA inputs

- Smoother graduation procedures

- Trade capacity building to boost programme utilization

- Potential expansion of covered goods

Additional priorities should include clearer renewal timelines ahead of expiries, modernised rules of origin for better global value chain integration, and enhanced eligibility review transparency. Most critically, preferences must extend beyond MFN rates to cover bilateral „reciprocal“ tariffs at minimum for key products given their greater relevance. Yet, given the administrations focus on the „America First“ agenda, an effective extension looks doubtful for now.

AGOA’s one-year lifeline reveals a programme caught in tensions. Created in a different geopolitical era, it must adapt to drastically changed US policy and trade realities. While the extension buys time, Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs have already killed its core duty-free promise. Repeated expiries, short-term extensions, eligibility disputes, and shifting tariff regimes create uncertainty at precisely when African economies need stability to attract foreign direct investment, create jobs, and integrate into regional and global value chains.

Policymakers face a clear choice: comprehensive reform prioritising mutual benefits, predictability, and long-term growth or continued marginalisation. Without a bold renewal, AGOA risks fading as a hollow political gesture rather than an economic opportunity. African policymakers‘ hands are not tied. Diversifying via swift AfCFTA implementation, trying to leverage China’s duty-free offers, and deepening EU partnerships provides leverage to press Washington for preferences that actually compete in today’s tariff landscape.

Schreibe einen Kommentar