The outcome of the Belém climate conference can be compared to a watered-down cocktail, a weak COPirinha, if you will: plenty of crushed ice, little substance to give it strength, and missing sugar in the form of climate finance to sweeten the deal. Hence, while the tumbler of climate diplomacy was well filled, its content hardly lifted spirits of anyone hoping for decisive climate action.

A Functional but Ineffective Multilateral Process

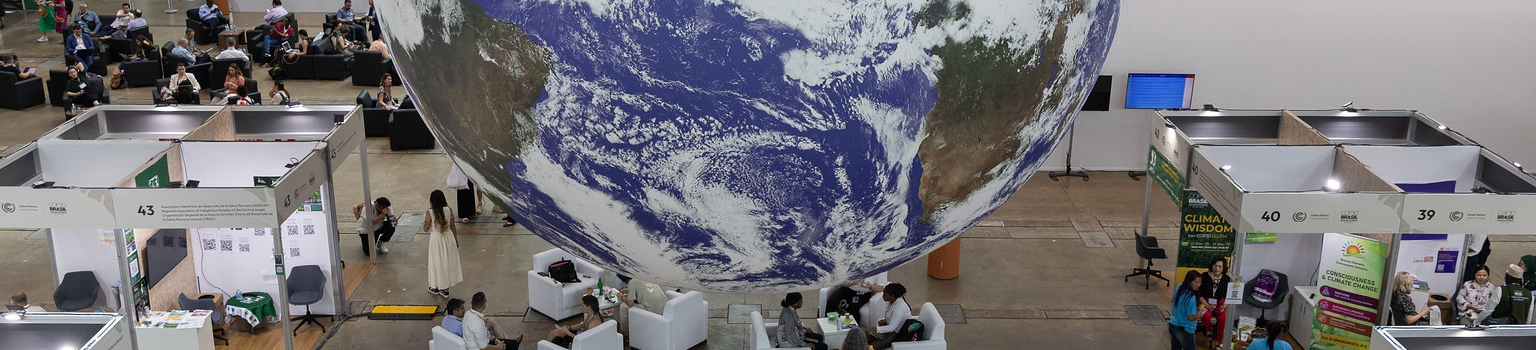

To be sure, “COP30” (the 30th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC) has sent out distinctly positive signals from the Brazilian Amazon to the world. It demonstrated that the multilateral climate regime remains functional—in spite of geopolitical disruption, fiscal stress, widespread mistrust, and even misinformation. Yet, functionality without effectiveness is a hollow consolation in the face of a worsening climate emergency. The acceptance of “overshoot” – that is temporarily exceeding the 1.5 degrees Celsius in average global warming established as core target by the Paris Agreement – as a central assumption of global climate governance is a case in point. What was once framed as an outcome that needs to be avoided has been virtually treated as a given in Belém.

Moreover, COP30 failed to deliver on several key milestones. While the Global Goal on Adaptation was “technically adopted,” haggling over indicators continues. The ambition gap to prevent or at least seriously minimise overshooting 1.5 degrees remains wide open. Progress on climate finance, too, fell severely short of what would be commensurate to last year’s compromise on the new collective quantified goal on climate finance (NCQG). And neither of the two “roadmaps” touted by the Brazilian COP Presidency—one on fossil fuel phase-out and one on deforestation—materialised. Still, the Presidency rallied a coalition of willing nations – a plurilateral initiative outside the UN climate process, signaling growing momentum for a global shift away from fossil fuels.

EU Leadership Undone by Strategy and Timing

The EU entered Belém on the back foot, exposed by delays in submitting its updated climate plan, technically referred to as Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). After protracted internal debates and a last‑minute compromise, the plan signaled wavering ambition and undercut credibility just as the EU sought to rally others behind stronger climate goals.

At COP30 itself, the EU was remarkably successful in redirecting attention away from its delayed NDC. The fact that global attention shifted from Parties’ ambition to the surprise initiative by the Brazilian Presidency to garner support for a global roadmap for transitioning away from fossil fuels served as a welcome distraction. Despite initial internal resistance—most visibly from Poland and Italy—the EU managed to present a unified position in support of the roadmap.

The EU thereby played a constructive role in securing consensus, preventing COP30 from collapse. Yet its diplomacy fell short of delivering greater ambition. Efforts to build alliances beyond Europe faltered, with many developing countries unconvinced by its focus on mitigation over adaptation. With adaptation finance a priority for climate vulnerable developing countries, the EU’s emphasis on the fossil fuel roadmap deepened divides — even appearing brazen in view of its late NDC.

Moreover, the EU failed to secure China’s support for more ambitious outcomes. In fact, tensions had been exacerbated prior to the COP by an exchange between EU Climate Commissioner Hoekstra and the Chinese climate envoy, with Beijing plausibly accusing the EU of hypocrisy over its criticism of China’s new NDC. Consequently, China and the EU arrived at COP 30 unaligned on key priorities.

Disappointment over failing to unite with developing countries and China – all under the shadow of an absent US – weighed heavily on the EU delegation. German environment minister Schneider said he had expected “a louder voice” from vulnerable nations and urged new alliances for a “new world order.” But the lesson is familiar: alliances must be forged before climate summits, not during them – a recurring takeaway as EU priorities remain misaligned with partner countries’ urgent needs.

European Hangover: Leadership Lost

The EU’s diplomatic missteps showed most clearly towards the end of the conference and for all the world to see. Shortly before the final plenary, commissioner Hoekstra stated in a press conference:

“If we deliver on mitigation here together, yes you can ask the EU to move beyond its comfort zone on the financing of adaptation. But only if the NCQG is respected in full, and only if all the mitigation elements are in the text.”

Yet, by openly making adaptation finance conditional on support for mitigation, the EU reinforced a widespread perception: that it consistently prioritizes mitigation over adaptation, and worse, that it treats adaptation as a bargaining chip rather than a pillar of climate justice. The question raised in the corridors was blunt: Does the EU have the money, or not?

Compounding the disenchantment, Hoekstra was quick to declare right after the closing plenary that the EU’s tripling of adaptation funding “means [no] additional cheque for European taxpayers” but rather a reallocation of EU contributions to international climate finance. This attempt to reassure domestic audiences openly clashes with the EU’s claim to global climate leadership. It exposes the tension between appealing to voters at home and meeting international expectations. As a result, the EU flip-flops between grand, cosmopolitan rhetoric on the global stage and beating around the bush at home. Belém thus exposed a dilemma in EU climate diplomacy: aspiring to lead the fossil fuel transition while relying on a delicate internal compromise.

Leadership is measured by the ability to foster global coalitions, to credibly engage partners’ interests, and to demonstrate political resolve and, indeed, financial commitments that match moral claims. Hence, if the EU is to position itself as a global leader once again—especially in a context where other major parties are backing out of multilateral commitments—it will need to reconcile internal political realities with external expectations more coherently than it did in Belém. The COPirinha metaphor thus applies not only to the overall outcome of COP30 but also to the EU’s performance: plenty of ice, weak substance, and a lingering aftertaste of missed opportunity.

Sobering Up: Steps Towards COP31

To regain momentum, the EU needs a coherent strategy as it approaches COP31. Co‑hosted by Türkiye and Australia, COP31 can be expected to spotlight the plight of Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Accordingly, adaptation and loss and damage finance will be high on the agenda, coinciding with clear expectations to top up the Least Developed Countries Fund and the Adaptation Fund and, not least, scoping the first replenishment of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, which is due in 2027.

Already, the EU faces mounting pressure to meet its financial obligations. Pointing to fiscal constraints will not serve as compelling excuses in the light of soaring military expenditures and persisting subsidies for fossil industries. Unless it chooses to abandon its leadership ambitions, the EU must rethink its approach to international climate finance— aligning with partner countries’ positions by treating mitigation and adaptation as a package, not as zero-sum bargaining chips. Moreover, it should strengthen alliances with high-ambition countries like Colombia and the SIDS to foster support for mitigation ambition and the global phase out of fossil fuels. To gain traction, indeed, to regain leadership, EU climate diplomacy requires a clear mandate from member states, sufficient financial leeway, and a genuine willingness to negotiate a comprehensive package with partners.

Schreibe einen Kommentar