Archives are the institutions of memory: categorising information about the past, they systematically store, preserve, and provide historically valuable records. This systematisation makes archives more resilient than what human memory can achieve, since humans recall information about a specific memory based on its “semantic” associative content. For science, archives “lay the foundations for future research and future memory”. They also shape and reconstruct the current collective memory in society by preserving physical records and offering the past to the present. As Cosetta G. Saba argued about digital archives, historical records also bear a function of cultural conservation – meaning that they also carry cultural context that causes the records to emerge and how they are seen. Even in longstanding democracies like the United States, recent controversies over book bans and ideological battles over national history education demonstrate how memory politics and archival control remain deeply contested terrains.

Digitising archives results in accessible archives for society. However, records are never neutral. Pasts of a nation could be regarded as sensitive and challenge how an archival institution organises and provides records. More complexity (and a risk of selective memory) is added by the fact that public archival institutions often only organise records they received from other institutions or persons. By comparing two countries arranging their past through archives, we can thus illustrate how society interacts with the stored information – and thus shapes its collective memory –.

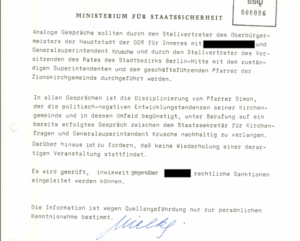

Let’s take Germany and Indonesia. Former East Germany’s Ministry of State Security (MfS or Stasi) and Indonesia’s Thirtieth September Movement (Gerakan 30 September, G30S) are the exemplars of sensitive periods which reflect how the work of archival institutions are shaping and shaped by society’s collective memory.

The comparison is justified for several reasons:

- Both countries had a challenging period related to a power transition in the past.

- Both records were produced by key state-bodies of citizens’ control in the past, the Stasi and Komando Operasi Tertinggi (KOTI).

- Then-records-now-archives are stored and managed at national-level archival institutions, das Bundesarchiv (BArch) and Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia (ANRI).

Archives digitisation: chances and challenges

Two factors drive archives’ digitisation processes: their use and their transience. The first is the use, i.e. frequent requests for access. Regulations require both Bundesarchiv and ANRI to provide information for everyone, and digitisation helps to achieve this. Digitised archives can also be used for organisational purposes, such as facilitating a smooth internal transfer between different departments within the archival institution. In ANRI, this internal digitisation process is specifically regulated.

The second reason is the finite lifespan of archival carriers. In the case of the Stasi Department, former MfS officers intentionally tore documents during the onset of the Peaceful Revolution. Hence, reconstruction and digitisation of Stasi documents became the central activity.

However, those digitisation drivers do not always push the openness and availability of sensitive archives. The Bundesarchiv might encounter no political sensitivity issues when providing Stasi documents for everyone. Nevertheless, ANRI is more careful when making the information regarding G30S from their KOTI documents available to the public. These differences emerge from variations in the content and context of the said documents and how relevant individuals utilise the information in those documents.

As for Stasi documents, there are three possible ways for everyone to gain access:

- When the access is demanded by people mentioned in the Stasi document.

Post-unification Germany has unlocked the possibility for (East-)German citizens to confirm whether or not the MfS surveilled them. Accessing relevant documents is offered by the department for everyone concerned about their past. - When the access is demanded for screening purposes.

Public and private agencies can gain access to Stasi documents to execute a screening process for their employees. This action will help the agency set the proper measures, for instance, by providing compensation and rehabilitation for the victims of the MfS. - When the access is demanded for research and media purposes.

Stasi documents could also assist these intents, as long as all required procedures are fulfilled.

Legislation (Stasi-Unterlagen-Gesetz, StUG) forms the basis for making Stasi documents accessible and utilisable, constituting the department to guarantee both the public’s right to information and individual’s right to privacy. The same performance could not be executed in providing KOTI documents in ANRI because it is not managed through a specialised division or regulated under a specific law. Thus, ANRI bears no special mandate for digitising and providing G30S files like the Bundesarchiv’s Stasi Department does with the Stasi documents.

Privacy issues are another subject of discussion in how these archive grant access for public use or not. Even though the Bundesarchiv and ANRI have a similar retention period, they manage the disclosure of archives differently. In ANRI, archive disclosure will be done after the retention period of 25 years is over, and it will be disclosed over the issuance of a decree from the Head of the institution. However, the disclosure of classified archives in ANRI may also be exempted if the files contain personal information.

On the contrary, the Bundesarchiv’s Stasi Department is mandated to provide all documents they hold. To ensure the individual’s right to privacy, Article 32 of StUG dictated that a copy of the Stasi records could be obtained as long as any „personal data have been rendered anonymous“. In other words, requesting copies of Stasi documents for research and media is possible as long as a redaction of any personal information follows it. This mechanism manifests „a successful model for balancing conflicts between transparency, privacy, and security“, as one expert from the Stasi Department stated while being interviewed for this study.

Contrasting handling of sensitive archives between Bundesarchiv and ANRI are caused by the regulations, which, in turn, relates to the public appetite towards the issue. At this junction, the public interacts with the written memory and later restructures its own collective memory.

Recollecting the past for the present memory

According to Paul Connerton, knowledge recollection of the past is done through communal practices performed by society, such as rituals, ceremonies, myths, and other activities. In line with this framework, let’s take a look into the access to and utilisation of archives, alternative forms of memory carriers, and the culture of remembrance.

Post-unification Germany was marked by a tremendous request from the German people for Stasi documents. The issue salience was at its peak then, serving people’s interest in inspecting, clarifying, rehabilitating, and uncovering the truth about their lives during the GDR authoritarian era. The Bundesarchiv’s Stasi Department, since the beginning of their work in 1990, recorded 7.518.186 requests and submitted applications for Stasi documents, utilised for various purposes as mentioned in the previous section.

Meanwhile, the G30S in Indonesia was undergoing a different sequence of events. Following the climactic moment of the „coup“ in 1965, Indonesia’s New Order regime made several attempts to dominate narratives about the G30S. Intentional obfuscations were manifested, for instance, through the creation of a state-sponsored movie called Treachery of G30S/PKI (Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI), which demanded mandatory viewings for Indonesians, especially school students. The same regime also produced the White Book on G30S to justify the mass arrests and killings of alleged Indonesia Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia/PKI) members. The repetitive communal practice, such as the yearly mandatory watching of the Treachery of G30S/PKI in Indonesia, is an exact manifestation of systematic remembrance.

It shows the act of government in selecting what to remember and which part of history should be forgotten. Images of such events in society and how they should be remembered are affected, where state actors decide and the collective memory is orchestrated. In a different vein, in Germany, a movie called The Lives of Others caught the public’s attention with its compelling depiction of the Stasi period. As a result, the movie has expanded new avenues for discussing the MfS era even further.

Lessons learned

Several key takeaways from this study are:

- Public service-oriented archives should serve everyone’s needs by providing access to archives rather than restricting it. In other words, archives should function as a safeguard against potential manufacturing of history and ensure access to factual records.

- Personal data should be managed with a balance between transparency, privacy, and security, for instance, by differentiating access and the usability of the archives. Archival institutions should fulfil their mandate of providing access to the public while also ensuring procedures are followed when an individual wishes to utilise the archive.

- Open and digitised archives can be utilised best if the existing social structure also encourages society to seek the truth. This reciprocal relationship makes the role of society in structural remembrance pivotal since it also decides whether or not the public will engage with and make the best use of the archives.

Acknowledgement

I am very grateful for the assistance from the German Federal Archive and the National Archives of Indonesia, especially for the dozens of experts from both institutions who are willing to share their perspectives, experience, and knowledge on this issue. High appreciation should also be extended to the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS), which hosted the researcher for three months in Bonn, and the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Indonesia, which sent the researcher to commence this fellowship programme.

The Promoting Research on Digitalisation in Emerging Powers and Europe towards Sustainable Development (PRODIGEES) programme has received funding from the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 873119. The programme connects eight countries on five continents to investigate digitalisation’s social, governmental, economic, and climatic impacts from local, national, regional and global perspectives.

The researcher’s motivation behind writing this topic is to urge Indonesians to remember their history. A necessary effort, which if pursued, could prevent Indonesia from re-entering the authoritarianism era we left 27 years ago. #CabutUUTNI #TolakDwifungsiTNI

Schreibe einen Kommentar