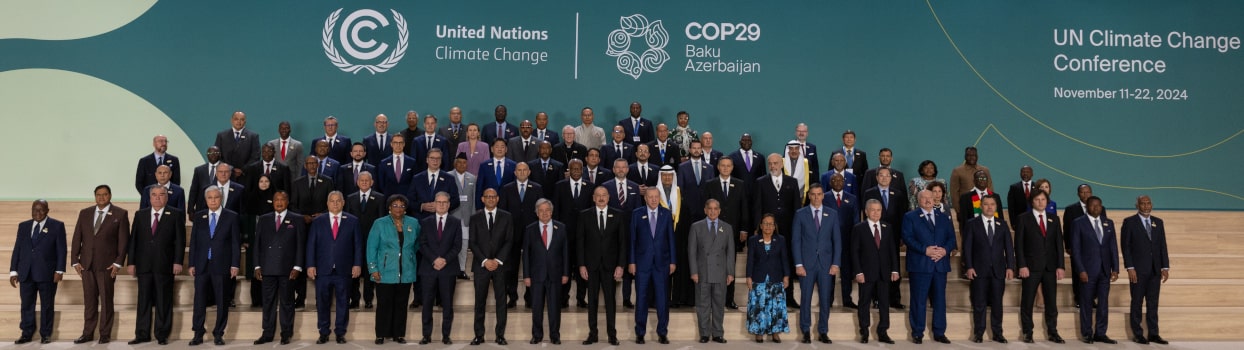

When the gavel went down in the early hours of Sunday morning in Baku and a decision was reached on the new collective quantified goals (NCQG) on climate finance it caused as much relief as disbelief in the room. The European Union (EU), represented by EU climate commissioner Woepke Hoekstra, praised the decision as “a start of a new era for climate finance”, while the group of least-developed countries stated to be “outraged and deeply hurt by the outcome of COP29“ and referred to “the bulldozed” NCQG as “a glaring symbol of this failure“. Some countries, notably India and Nigeria, openly objected the adopted decision on the NCQG, calling the „document little more than an optical illusion” – prompting loud applause in the plenary.

The $300 billion compromise: reflecting deep divisions and undermining Paris Agreement commitments

The new number, which represents a tripling of the $100 billion goal formally agreed upon in 2009 to at least $300 billion per year by 2035, is far from signalling ambition and does not reflect the urgency of the needed support. Essentially, this goal does not demand much additional effort from traditional donors, as it does not account for inflation and includes contributions from multilateral sources and the private sector. It effectively ropes in voluntary contributions from developing countries, such as China, coupled with climate-related finance mobilized by multilateral development banks (MDBs), to which emerging economies also contribute. The $1.3 trillion in climate finance by 2035 aspired by developing countries based on scientific calculations of their needs made it to the decision text but only with the vague wording that all actors should work together to achieve this.

To be sure, the new climate finance goal is not merely about scaling up climate finance. Its aim was to provide a globally agreed framework that could ensure a fair allocation of limited resources, improve access, enhance effectiveness and gurantee transparency. Yet, certain provisions in the text appear to weaken commitments under the Paris Agreement and pave the way for potentially risky diversions. First, the new goal assumes a prominent role for MDBs, which are neither accountable to the COP nor guided by the core principles of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, such as those related to equity. Second, the agreed text includes neither a specific grant-based core of public finance nor minimum allocation floors for the most vulnerable countries, nor concrete access targets. It also lacks dedicated support for loss and damage. Hence, there is a palpable danger that longstanding issues related to limited access and inadequate support to vulnerable countries will now be reinforced. Lastly, there are also no safeguards in place to ensure transparency and to prevent the creative accounting and double-counting of development and climate finance under the new goal. In fact, the wild west of climate finance is likely to become even wilder under the new goal.

Baku to Belém Roadmap: a second chance to raise climate finance ambition?

The “Baku to Belém Roadmap to 1.3T” that made it into the text, aims at scaling up climate finance to developing countries, and has been orchestrated by Colombia with the support of an alliance of developing countries from Latin America, Africa and Asia. While this has now been presented by some as a means to mobilise and increase private climate finance, this is arguably not the primary objective the initiators had in mind. Much rather the idea is to tap innovative sources of finance, notably including instruments like solidarity levies, taxes on fossil-fuel extraction, on aviation and shipping, and taxing the super-rich to unlock greater financial scope including “grants, concessional and non-debt creating instruments, and measures to create fiscal space“. Indeed, the Baku to Belém roadmap idea emanated from the frustration over the lack of progress developing countries were able to achieve at COP29 as well as the unsatisfactory scale of the NCQG itself.

Rebuilding the EU’s leadership

The newly found compromise is very fragile, with much trust squandered in its creation. With the incoming Trump II presidency and its expected position on climate governance – probably non-cooperation, possibly even outright obstruction – the EU urgently needs to reinvest into its self-proclaimed climate leadership role of which too little was seen in Baku. To be fair, European countries are also under pressure domestically, facing budget restrictions and tough challenges from populist right-wing parties that are blatantly questioning international commitment and spending. What happened in Baku, however, must be seen as a diplomatic failure rather. The EU’s tactics of putting a number for the NCQG on the table at the very last minute has been widely criticised (including by the Azerbajani Presidency), likewise the EU’s move to portray a dissatisfying goal as a success did not go down well with developing countries. Generic statements like „not perfect, but an important step forward,“ which could apply to almost any COP, trivialise the significance of the Baku outcome, thereby adding insult to injury from the perspective of climate vulnerable developing countries.

Despite an outcome of the climate finance negotiations that aligned with the EU’s major objectives, the EU remained dissatisfied with the lack of progress in the mitigation work programme and the lack of support for greater emission reduction ambition from other countries. Yet, at COP30 in Brazil, the negotiations will centre largely on how to accelerate this ambition, with countries due to table the next iteration of their national climate plans (Nationally determined contributions – NDCs). For many developing countries, these NDCs will understandably be highly conditional on the prospect of external financial support. The newly adopted NCQG fails to assure developing countries, likely leaving them hesitant to increase ambitions as desired by the EU. To gain Global South support for ambitious emission reductions, the EU must take the Belém roadmap seriously and address the legitimate concerns of developing countries in a constructive manner.

In short, the prevalent flaws in the existing climate finance architecture have not vanished by ignoring them in Baku. Considering the political economy within the EU and the implications for scaling up grant-based finance, the EU should proactively advance much-needed improvements to the quality of climate finance as a means to accomodate some of developing countries pressing concerns. For starters, the EU should embrace the Belém roadmap as an opportunity to collaborate with developing countries on resolving critical quality issues of climate finance and create a common understanding of what constitutes good, affordable, transparent, and effective climate finance in the first place. With that, all parties could set out to pick up the pieces from Baku and forge a unified path forward. Ultimately, parties should stop quarreling over whether the glass appears half full or half empty, but need to find feasible ways to top it up.

Schreibe einen Kommentar