Content

Why transnational cooperation as a lens?

How do we approach the topic?

The role of development cooperation and beyond development cooperation

Introduction: transnational cooperation – an explorative collection

Sven Grimm & Stephan Klingebiel

Abstract

The present collection of short papers is an experimental, explorative and introspective German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) project on international and transnational cooperation for development and sustainability. It is the product of internal brainstorming discussions at IDOS in mid-2022 that aspired to conduct a preliminary, exemplary mapping of the use of “transnational lenses” and their understandings across various work strands at the institute. This might lead to new questions in our work, or it might simply be an attempt to look at our topics of interest with a different perspective.

Why transnational cooperation as a lens?

The term “common good” aims at the (sustainable) well-being of societies and, by extension, the individuals living in them (Messner & Scholz, 2018). It can be pursued nationally by public actors (governments, their agencies and parliaments), but not exclusively by them, as society is broader than the state administration and the relevant interaction of actors on many levels (particularly the subnational and local levels). Cross-border, if not global interdependencies are a fact of life, summarised under the term “globalisation” (the intensification of cross-border exchanges of goods, services, ideas and human mobility).

Awareness about living in the Anthropocene (UNDP [United Nations Development Programme], 2020), in which human activities have an impact on every part of the planet, makes cooperation even more important, as interconnectivity means that the common good cannot be achieved only at the national level. Public and individual actions – at least in their effects – never fully stop at state borders. At the very least they require coordination, if not cooperation, on a broad range of themes, from pollution mitigation and action against the spread of diseases, to value chains that stretch across borders, as well as ocean governance, climate policy and other actions on the global commons.

The listed examples already showcase the strong need for coordination – if not cooperation or even collaboration – beyond national borders on a broad range of topics, so that one country’s well-being interacts positively with the situation elsewhere and does not negatively affect others. Conceptually, the global common good is more than the sum of its parts and will need to not only involve states, but also exceed them (synergies of cross-border and multi-stakeholder cooperation).

Interdependencies in most policy areas require various states’ involvement through coordinated policy-making. Yet, non-state actors such as the private sector, civil society organisations (CSOs) and academia, for example, are also needed in multi-stakeholder relations (see the contribution by Furness on state–society relations in the context of social contract debates), as well as individuals. International organisations also often play an important role (see the contribution by Wehrmann and Weinlich). Finding solutions is already a difficult task within clearly delimited groups because of a number of collective action problems (discussed, inter alia, by Olson, 1965, and Ostrom, 1990), and the “orchestration” of actors is an enormous effort (Paulo & Klingebiel, 2016). Yet, the setup becomes much more ambitious for the global common good. Solutions typically need to be cross-border in nature and bring together different types of actors (private and public) from different levels (local, national, regional and global). Finding solutions to transnational challenges requires high-quality cooperation or even collaboration (Chaturvedi et al., 2020), that is, it goes beyond mere coordination of national policy processes.

Against this background, we regard transnational cooperation as a crucial perspective for organising collective action in pursuit of the global common good. Unlike international cooperation, transnational cooperation regularly involves at least one non-public or sub-national actor, that is, it does not exclusively take place in a nation-state world. Not only in this respect is the example of Sámi-EU relations an important illustration (see Götze’s contribution).

Transnational cooperation can be well-established or ad hoc, and it can create structures and become institutionalised. It is reality in many ways: The private sector is often organised in transnational forms, and research is not bound to a specific country or academic institution and operates to a large extent in a transnational way. Additionally, transnational actions might not require the systemic coherence of states, but instead require the convergence of interests and agreement on a certain set of norms among actors from different settings and across borders.

The concept of transnational cooperation is not necessarily inherently “good”. It is important to question the purpose of transnational cooperation, as it can both foster the global common good and be used for the selfish intents of a narrow set of actors (e.g. lobbying in the interest of profits). It can also become a proxy or disguise for nation-state action. Some networks can act on behalf of a state or with state-like intentions. Historically, transnational activities by private entities were used to expand economically and created precursors to colonial domination, as with merchants’ associations that had de facto state-like powers. Organisations such as the Dutch East-India Company or different British “chartered” organisations operated as “company-states” and were intentionally instrumentalised to expand empire (Phillips & Sharman, 2020). Extremist organisations claiming religious legitimacy, such as the “Islamic State”, can challenge and try to replace state authority. And certainly, criminal activities can be organised transnationally, with the mafia and transnational gangs (Paarlberg, 2022) providing vivid examples of actions taken against the common good; and, for instance, cybercrime, which almost by definition transcends borders (for a definition, see United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, s.a.).

How do we approach the topic?

Our specific angle of enquiry and critical reflection is directed by a global common good lens, that is, beyond the interests of a limited set of actors or individual states. In an explorative approach, we want to pursue the questions of where and how transnational cooperation proves to be effective for transformational policy-making towards the global common good:

- Where (thematically) do we observe a particular relevance of non-state actors (with or without an interface to state actors) in cross-border cooperation for the global common good?

- Do we see well-functioning transnational cooperation – and which key structural and/or circumstantial features are deemed relevant for this success? Where do we see the opposite (non-functioning areas of transnational cooperation)?

- What are the relevant mechanisms of coordination/cooperation/collaboration/orchestration (including power aspects and capacities such as individual skills as well as interconnectedness of knowledge systems)?

- How do we address the transnational cooperation dimension in our activities relating to research and policy advice?

In this explorative exercise, we do not claim comprehensiveness. Rather, the aim is to engage in a discussion on our multi-perspectivity at IDOS and start a conversation about our understanding. The present papers consequently do not follow one approach, nor do they constitute a consolidated debate, neither collectively nor individually. They are meant to be contributions for debate and can constitute starting points, not least within our research clusters and across the dimensions of the IDOS mandate, that is, research, policy advice and training on cooperation for development and sustainability.

The role of development cooperation and beyond development cooperation

In our view, the codification of the “global common good”, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be understood as human-centred approaches informed and sharpened by debates on topics such as “capabilities approach”, “human development” and “development as freedom” (Sen, 1989; UNDP, 2020). In many ways the 2030 Agenda and its SDGs illustrate that international cooperation (including development cooperation) remains important.

Within the rationale of the 2030 Agenda, SDG 17 focusses on partnerships and is needed to push for the goals defined in the 2030 Agenda, including SDGs 1 to 16, and the cross-cutting issues (“leave no one behind”) as well as the universal nature of the 2030 Agenda. However, for a number of decades (see e.g. Nye & Keohane, 1971), we have known that transnational actors and transnational cooperation are essential to get a better understanding of the challenges (e.g. the transnational character of climate change, conflicts or the Covid-19 pandemic) and solutions (Klingebiel et al., in press; Wehrmann, 2020).

Traditionally, the nation-state and its governments form the most important actors when it comes to cross-border cooperation. This is why international cooperation and all relevant platforms and mechanisms are mainly rooted in nation-states. Cross-border cooperation is accordingly organised. This is true for the traditional way in which countries conduct their relations with other countries, typically in the ministries in charge of foreign affairs. This is also the case with development cooperation. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and its Development Assistance Committee (DAC) invented the concept of official development assistance (ODA) (Bracho, Carey, Hynes, Klingebiel, & Trzeciak-Duval, 2021). Thus, development cooperation is initially a way to create a modality (concessional, respectively grant arrangements) for a purpose-specific (economic and social welfare) and mainly intergovernmental cooperation.

Yet, also in development cooperation, there is a strong need to focus on non-public actors. The private sector, CSOs, academia and the media are among the most important non-public actors (see Gutheil and Nowack’s CSO examples; Bergmann, Erforth and Keijzer provide an illustration for the private sector). Many of those actors are transnational in nature, for instance enterprises or philanthropic non-profit institutions. The transnational character of cooperation is to a large extent the reality of cooperation nowadays. At the same time, transnational cooperation is also a requirement for a higher level of effective and inclusive cross-border cooperation.

The perspective of transnational cooperation can be useful for working on concepts in support of the provision of global (or transnational) public goods (Kaul, 2012; Klingebiel, 2018; Nordhaus, 2005). This perspective is essential to design development cooperation’s contribution towards furthering a “global common good”. Existing forms of development policy and development cooperation need to be part of such an approach. The policy field is crucial for this task, and it offers experience in pursuing an agenda that intentionally goes beyond self-interest and a self-centred perspective. Furthermore, it is used to provide norms and standards for how to organise cooperation (e.g. the ODA definition [with all its limitations]).

Even though development cooperation might form relevant starting points for such a discussion, it is also very clear that the policy field is still biased in favour of government-to-government or at least international cooperation. This is, of course, also due to the fact that ODA is defined as an instrument provided by “official” actors. There is probably no declaration or conference outcome document that lacks an emphasis on non-public actors. However, as we understand, for example, from the interactions between ODA actors and the private sector, it is difficult in reality to upgrade development cooperation to a level where it can claim to be transnational in nature (see Haug and Taggart’s contribution).

The role of knowledge cooperation

Working for the global common good, as a precondition, requires recognition of a community of fate on our planet. We cannot presume that cooperation necessarily builds on the same value system, even though collectively held beliefs shape interests and identities (Finnemore & Sikkink, 2001; Wendt, 1972). An important dimension at work in the global common good thus is the exchange and agreement between diverse actors on what constitutes it, and ideally what to prioritise in addressing specific challenges. The 2030 Agenda, despite imperfections, is the politically agreed embodiment of the global common good. Academic debate needs to critically reflect on the agenda itself. Furthermore, any institute with the vocation to be policy-relevant, such as IDOS, also needs to analyse and critically accompany the implementation of the Agenda. How we interpret certain goals and how we make sense of the synergies and trade-offs between them is an ongoing matter in a dynamic, real world; it requires cooperation beyond disciplinary or professional delineations – and across national borders. This, certainly, is not unaffected by power relations between actors, as research about the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, has highlighted on a number of occasions (Corbera, Calvet-Mir, Hughes, & Paterson, 2016; Ketcham, 2022).

Transnational cooperation is thus both a research topic for IDOS and part of its vocation. Like other academic actors, IDOS engages in, facilitates and nurtures the exchange of views. These allow for the development of ideas about what constitutes the global common good, lead to enquiries on how societies perform while pursuing it and encourage the development of ideas on how best to achieve it.

In its focus on development and sustainability, IDOS needs to work with institutions, interests, mechanisms and policy content, but it is also well-advised to explore underlying norms and knowledge systems and their roles in policy-making. This includes reflecting on the institute’s own contributions and position in academic and training relations. A premise of IDOS’ work is that collective and transnational joint learning in diverse groups on globally and locally relevant issues can initiate the practice that reinforces cooperation. This includes considerations on power relations, which Ruppel and Schwachula have put at the centre of their contribution to this collection.

If successful, building transnational networks thus serves both a self-interest of IDOS as a research institution operating in epistemic communities, and as a precondition for effective solution-seeking across borders for the global common good. How do our cooperation formats, including our training, create social infrastructure for – and thus contribute to – transnational cooperation? What assumptions is our training based on, and what lessons do we draw from the interactions of different groups? Do we foster transnational cooperation for the global common good? And where are the possible limitations in approaches beyond the mere scale of activities that we need to consider? A number of aspects are reflected in the contributions from our team on knowledge cooperation, understood as (early) career development and networking.

Transnational cooperation as strategic – as opposed to coincidental – interaction occurs “when different actors adjust their activities and behaviour in order to obtain benefits”, often in the form of increased knowledge (Vogel, Schwachula, & Reiber, 2019). Through co-creations of knowledge, transnational cooperation can pave the way towards facilitating transformative changes at the global and local levels, referred to as a global epistemic equality (Shamsavari, 2007, in Vogel et al., 2019). As a specific focus in joint knowledge creation, our research thus analyses and identifies the required skills and competences needed in inter- and transnational cooperation, as used by Reiber and Eberz as a starting point for reflections in their contribution to this collection on training formats. For research cooperation, Rafliana and Hernandez provide examples in their contribution.

Interactions that shape the global common good need to consider both institutions and individuals, as well as the systemic context within which both operate. It is important to acknowledge that there is a universe of reasoning as to why globalisation is relevant. This relates to the cultural diversities and different social history contexts (Duscha, Klein-Zimmer, Klemm, & Spiegel, 2018), many of which challenged the way (transnational) cooperation is navigated and interpreted by the different actors and agencies involved (e.g. Benabdallah (2020) on China and its building of knowledge production networks; Fues (2018) on Managing Global Governance). Local and sub-regional issues such as conflicts, political (dis)integrations, migrations, digital communication, environment and poverty are entangled and undetachable in the shaping of global discourse and knowledge. And yet, despite these differences, some lessons can be learnt on how to create and sustain transnational networks, as Johanna Vogel points out in her contribution on lessons from the literature and IDOS’ own experiences.

Academic cooperation needs to involve young professionals, both from academia in emerging countries and African states as well as in the areas of political decision-making and civil society, particularly taking into account the increasing influence of think tanks in the Global South. It also requires catalysts to provide a critical and open environment for dialogues and interactions, as these are among the neglected aspects in knowledge creation and knowledge cooperation relations (Lee, Liu, & Wu, 2011). Cooperation enables all actors to gain insights into the common responsibilities but different roles in the global system, the different discourses and logics of action as well as underlying value and belief systems. These insights are crucially important and should be an integral part of the criteria for research excellence, as they are indispensable for a meaningful analysis of and recommendations for the global common good. Consequently, IDOS’ activities seek interactions and network-building, both at the individual expert level and at the institutional level, aiming to recognise social challenges from multiple perspectives and to work on them with a view towards cross-regional solutions as well as nurturing global change-making initiatives.

Joint learning experiences in the formats offered by IDOS create strong foundations for networks in different regions, target systems and aim to improve the institute’s research, advisory services and training activities in a goal-oriented manner. Joint research and advisory formats with alumni and our network continue beyond the respective course participation. Through policy dialogues and knowledge cooperation (joint knowledge production) in internationally oriented training activities, the institute aspires to facilitate the development of common perspectives and priorities with regard to dealing with global challenges. Knowledge, institutional problem-solving abilities as well as personal skills are developed and trained for together. By networking with trainees and partner institutions and funding innovative projects, actors could generate “catalytic cooperation” (Hale, 2020) for various shared purposes of sustainable development. Eva Lynders argues in her contribution that this enables individuals – often in networks – to engage in transformative change for the global common good.

References

Benabdallah, L. (2020). Shaping the future of power – knowledge production and network-building in China-Africa relations. University of Michigan Press.

Bracho, G., Carey, R., Hynes, W., Klingebiel, S., & Trzeciak-Duval, A. (Eds.) (2021). Origins, evolution and future of global development cooperation: The role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) (DIE Studies 104). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Chaturvedi, S., Janus, H., Klingebiel, S., Li, X., De Mello e Souza, A., Sidiropoulos, E., & Wehrmann, D. (2020). Development cooperation in the context of contested global governance. In S. Chaturvedi, H. Janus, S. Klingebiel, X. Li, A. De Mello e Souza, E. Sidiropoulos, & D. Wehrmann (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of development cooperation for achieving the 2030 Agenda (pp. 1-21). Palgrave Macmillan.

Corbera, E., Calvet-Mir, L., Hughes, H., & Paterson, M. (2016). Patterns of authorship in the IPCC Working Group III report. Nature Climate Change, 6(1), 94-99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2782

Duscha, A., Klein-Zimmer, K., Klemm, M., & Spiegel, A. (2018). Understanding transnational knowledge. Transnational Social Review, 8(1), 2-66.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (2001). Taking stock: The constructivist research program in international relations and comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 4(1), 391-416.

Fues, T. (2018). Investing in the behavioural dimensions of transnational cooperation: A personal assessment of the Managing Global Governance (MGG) Programme (DIE Discussion Paper 12/2018). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Hale, T. (2020). Catalytic cooperation. Global Environmental Politics, 20(4), 73-98. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00561

Kaul, I. (2012). Global public goods: Explaining their underprovision. Journal of International Economic Law, 15(3), 729-750.

Ketcham, C. (2022). How scientists from the “Global South” are sidelined at the IPCC. The Intercept, 17 November 2022. https://theintercept.com/2022/11/17/climate-un-ipcc-inequality/

Klingebiel, S. (2018). Transnational public goods provision: The increasing role of rising powers and the case of South Africa. Third World Quarterly, 39(1), 175-188.

Klingebiel, S., Hartmann, F., Madani, E., Paintner, J., Rohe, R., Trebs, L., & Wolk, L. T. (In press). Exploring the effectiveness of international knowledge cooperation: An analysis of selected development knowledge actors. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lee, W.-L., Liu, C.-H., & Wu, Y.-H. (2011). How knowledge cooperation networks impact knowledge creation and sharing: A multi-countries analysis. African Journal of Business Management, 5(31), 12283-12290. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.522

Messner, D., & Scholz, I. (2018). Globale Gemeinwohlorientierung als Fluchtpunkt internationaler Kooperation für nachhaltige Entwicklung – Ein Perspektivwechsel. Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, 11, 561-572.

Nordhaus, W. (2005, May 5). Paul Samuelson and global public goods: A commemorative essay for Paul Samuelson. Yale University.

Nye, J. S., & Keohane, R. O. (1971). Transnational relations and world politics: A conclusion. International Organization, 25(3), 721-748.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Paarlberg, M. A. (2022). Transnational gangs and criminal remittances: A conceptual framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 10, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-22-00297-x

Paulo, S., & Klingebiel, S. (2016). New approaches to development cooperation in middle-income countries: Brokering collective action for global sustainable development (DIE Discussion Paper 8/2016). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Phillips, A., & Sharman, J. C. (2020). Outsourcing empire: How company-states made the modern world. Princeton University Press.

Sen, A. (1989). Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19(1), 41-58.

Shamsavari, A. (2007). The technology transfer paradigm: A critique (Economics Discussion Paper 4). Kingston University.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2020). The next frontier: Human development and the Anthropocene (Human Development Report 2020). https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2020

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (s.a.). Transnational organised crime. https://www.unodc.org/ropan/en/organized-crime.html

Vogel, J., Schwachula, A., & Reiber, T. (2019). Bridging the North-South knowledge divide through transnational knowledge cooperation: Towards a research agenda. In Proceedings of “International conference on Sustainable Development 2019: Good practice: Models, partnerships, and capacity building for the SDGs”. https://ic-sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/johanna_vogel.pdf

Wehrmann, D. (2020). Transnational cooperation in times of rapid global changes: The Arctic Council as a success case? (DIE Discussion Paper 12/2020). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Wendt, A. (1992). Anarchy is what states make of it: The social construction of power politics. International Organization, 46(2), 391-425.

Part 1: The role of development cooperation and beyond development cooperation

Legitimacy challenges in inter- and transnational cooperation

Dorothea Wehrmann & Silke Weinlich

Abstract

Inter- and transnational formats of cooperation are increasingly contested at a time when both are needed more than ever to address globally shared challenges. This paper focusses on the origins of contested legitimacy in inter- and transnational cooperation. Legitimacy is understood here not as a quality that an actor possesses or not, but one that results from social processes (see also Tallberg & Zürn, 2019). The paper introduces different formats for inter- and transnational cooperation. First, we show that despite an overall shift towards allowing more transnational actor participation in international decision-making, resistance against meaningful and comprehensive participation remains high among a substantial group of states. Also, among transnational actors themselves, questions concerning access and participation remain disputed. Second, the paper argues that different cooperation formats need to take into account the unequal capacities and capabilities of actors in a more extensive way. To enhance the legitimacy – and potentially also the effectiveness – of cooperation formats, these differences should be considered in institutional set-ups, facilitating not only participation but also real contribution. For this, more attention needs to be paid to the differences also among non-state actors, which are often classified according to their types but take different roles depending on the format of cooperation and the governance levels at which they operate.

Introduction

The need to intensify global cooperation is dramatic. The number of people affected by hunger, disease and violent conflicts has significantly increased, and new scientific evidence illustrates that global warming is occuring much faster than researchers expected just last year[1] (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022; World Bank, 2022). Since 2015, when the international community agreed on the global goals defined in the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, global challenges multiplied and appear to be even more complex to solve. Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is particularly the lack of coordination, funding and commitment-dominated discussions that have led to the actions of the contracting parties falling behind their visions. More recently, international cooperation (Chaturvedi et al., 2021) and international organisations (Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichel, & Weise, 2019; Steffek, 2003) themselves are increasingly contested, not least because of the rise of authoritarian regimes and populism.

In light of the exacerbating global challenges, one strategy to motivate cooperation has been to intensify collaboration with like-minded partners. In that regard, the G7’s aim to set up an intergovernmental Climate Club (G7 Germany, 2022a) is an example of a format originating from “dissatisfaction with the multilateral [UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] process” (Falkner, Nasiritousi, & Reischl, 2021). The Climate Club shall accelerate action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by focussing explicitly on the industry sector (G7 Germany, 2022b). Although this aim supports the implementation of the Paris Agreement, the Climate Club still “faces an international legitimacy deficit”, because it is not clear yet how this new and separate format of cooperation will relate to, cooperate with and potentially weaken the existing multilateral climate regime (Falkner et al., 2021).

In addition to the formation of new inter-state fora, over the past decades various partnerships with state and non-state actors have formed to tackle shared challenges. The number of public–private partnerships; multi-actor partnerships and platforms; alliances and networks is still growing, and many of them are transnational in scope.[2] These formats of cooperation follow different purposes and operational structures. They range from voluntary arrangements to contractual arrangements, and they differ in their mandates, objectives, structure and levels at which they primarily operate. They follow different internal logics and organising principles, which are shaped by their purposes (knowledge partnerships, partnerships to provide services, etc.) and the types of actors engaged (Wehrmann, 2018). Similar to inter-state fora such as the Climate Club, these partnerships also face legitimacy challenges.[3] In the field of development policy, for example, partnerships with private actors have been formed to increase global investments for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Even in initiatives that aim at including small and medium-sized enterprises (Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, 2022), however, “private-sector voices are dominantly from transnational corporations and the financial sector” (Mawdsley, 2021, p. 52). These settings thus privilege and strengthen the sway of those that already have greater influence and seek to comply with – and tend to prioritise – their own financial logics. At the same time, the effectiveness of these new partnerships is also under debate (see Beisheim & Simon, 2018).

Instead of establishing a new format for cooperation, another strategy to motivate cooperation for tackling shared (global) challenges is to include more actors and enlarge existing inter-state settings, also with non-state actors. Although a larger number of actors engaged generally tends to strengthen the legitimacy of these settings, it also often encourages discussions on their efficiency and effectiveness (Kankaanpää & Young, 2012), the distribution of power in these settings and the need to adapt institutional designs (Knecht, 2020). Similar to the legitimacy challenges experienced in other partnerships – also in fora for cooperation that seek to be inclusive and expand – the unequal capacities and capabilities of actors impede their means to contribute and influence cooperation, and ultimately to identify with results. Consequently, outcomes are likely considered unjust and fail to encourage real (transformative) change.[4]

This paper contributes to the discussion on how legitimacy issues can be addressed in the inter- and transnational formats of cooperation needed for advancing the implementation of the global goals. More specifically, it introduces two cases. A snapshot analysis of the United Nations (UN) and the ongoing process to modernise it and link it with various club formats shows that resistance to opening the UN up to participation of non-state actors remains difficult. An analysis of the Arctic Mayors’ Forum (AMF) shows why, in order to advance legitimacy, it is necessary to consider unequal capacities and capabilities of the actors engaged in all kinds of cooperation formats, but also the level of governance at which they operate and, respectively, their relations with other entities.

Opening up the UN: a test case for contested legitimacy

Legitimacy standards for international organisations have shifted towards norms of inclusiveness (Dingwerth et al., 2019). This is also evident at the UN. Since the Earth Summit in Rio, non-state actors have been involved in major UN decision-making processes in the area of sustainable development and organised as “major groups and other stakeholders”.[5] In these groups, non-state actors from different states come together and cooperate in order to influence global decision-making. The groups played a particularly prominent role in the negotiations leading up to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and are now also extensively involved in the follow-up processes in the High-Level Political Forum (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2021). At the same time, despite opening up to non-state actors, the UN remains the bulwark of national sovereignty. Many states, in particular autocracies like Russia and China, as well as other states from the Global South continue to be eager to restrict the access of non-state actors in negotiations (Beisheim, 2021, p. 15). But states from the Global North, while often encouraging the consultation and input of non-state actors to UN decision-making, are also hesitant to relinquish the primacy of intergovernmental decision-making.

In response to the UN’s 75th anniversary, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for an overhaul of the UN and presented a plethora of proposals with a view towards an “inclusive and networked multilateralism”, comprised in the report “Our Common Agenda” (United Nations, 2021). In an unprecedented move, the Secretary-General did not shy away from addressing clubs and other governance formats outside of the UN that include many stakeholders, but instead advocated for their greater use in order to implement global goals. Many of the proposals – ad hoc, thematic emergency platforms; a Council on future generations; a biannual summit between the G20, the UN Economic and Social Council, international financial institutions and the UN Secretary-General – go beyond intergovernmental policy-making (see also Schnappauf et al., 2022). The report is an important input into a state-led process that leads up to the Summit of the Future, planned for 23 and 24 September 2024.

Initial member states’ reactions to the recommendations for opening up UN decision-making were mixed, as the consultations in April 2022 showed (President of the UN General Assembly, 2022). Opposition to giving a greater say to non-governmental actors is rooted in concerns about national sovereignty, but also fears that it might open up the UN (even more) to corporate interests. Moreover, non-state actors involved in ongoing UN processes, for example on sustainable finance, were far from embracing ideas for more openness towards external stakeholders and interactions with club formats. They expressed fears that the existing UN processes exhibiting established forms of cooperation with transnational actors might be sidelined by new formats, and that these could also easily be compromised by greater corporate influence (Civil Society Financing for Development Group, 2022). The policy process leading up to the Summit of the Future is unfolding on several tracks and is set to cumulate in a political declaration that might or might not authorise and enable greater participation of non-governmental actors at the UN. The battle over the access and influence of transnational actors is ongoing across all tracks, be it in negotiations on the modalities of the summit – which determine the extent transnational actors can contribute to shaping the input into the summit – or negotiations on the actual content of proposals, such as the establishment of a Youth office and a declaration of future generations.

Non-governmental actors organised as transnational groups have become accepted actors in UN decision-making, although their influence remains contested, and their formal participation rights remain restricted. The Summit of the Future will provide an opportunity to open up the UN to non-governmental actors and bring them into various new governance formats. Yet, given the opposition of states such as Russia and China against greater participation of civil society actors and the overall geopolitical climate, a breakthrough remains rather unlikely. On the one side, such a failure to modernise the UN and institutionalise the problem-solving capacities of transnational actors within its structures seems problematic. On the other side, major legitimacy issues concerning greater stakeholder participation in global governance need to be resolved in order to increase – and not undermine – the legitimacy of the UN in this manner.

Undermining or bridging national governments? Cities alliances and their interactions with international organisations

International organisations such as the UN more often seek to include non-state perspectives in their negotiations. In the specific context of climate governance and for sustainable development approaches, cities, regions and businesses in particular shall “help ensure that global climate efforts are implemented in a way that supports, rather than hinders, local sustainable development” (Kuramochi et al., 2019, p. 6). As transnational actors, “cities alliances” are perceived as carrying a lot of potential to solve global challenges. Yet, their interactions with international organisations are mostly unregulated – also in regions where intensive cooperative structures already exist, as with the Arctic.[6] Moreover, cities alliances are special kinds of non-governmental actors. Different to other non-governmental actors, the collaborating actors here are elected representatives (Wehrmann, Łuszczuk, Radzik-Maruszak, Riedel, & Götze, 2022). It is estimated that nearly 300 city networks exist at present, and most of them unite cities from different countries (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020).

The Arctic Mayors’ Forum is an example of a cities network that unites cities located in different countries and seeks to contribute to international cooperation. Due to the rapidly changing environment, and in conjunction with the global urbanisation trend also in the Arctic, cities have been subjects and objects of change and have cooperated bilaterally with twin-cities/ sister-cities for decades.[7] However, with the establishment of the AMF in 2019, a new formal channel for local communities was added to the Arctic’s regional governance system. The 14 current municipal leaders from the “Arctic 8” that are engaged in the AMF intensified their collaboration to introduce local knowledge to policy-makers at the national and regional levels, as these policy-makers have often been criticised for neglecting local realities. To “voice their opinion” (Arctic Mayors’ Forum, 2022), the AMF, among others, seeks to become an observer to the Arctic Council, which is the main intergovernmental forum in the Arctic, with transnational cooperation being an essential part of the Arctic Council’s DNA.[8]

The Arctic Council’s mandate[9] covers the main drivers of change for Arctic municipalities. However, on 3 March 2022 the Arctic Council decided to pause all official meetings for the very first time due to the war in Ukraine. On 8 June, the “Arctic 7” (all Arctic states minus Russia) declared “a limited resumption” of their work in the Arctic Council “in projects that do not involve the participation of the Russian Federation” (US Department of State, 2022). Given these circumstances, it is not clear yet whether or not the AMF will pursue its application for observer status to the Arctic Council. In general, the Arctic Council is a rather inclusive setting for cooperation that has grown continually since its establishment in 1996. Particularly Indigenous organisations have a unique say in the Arctic Council, even though only Arctic states have voting rights. As permanent participants, Indigenous organisations obtain full consultation rights.[10] Indigenous citizens represented by Indigenous organisations thus have a greater say than non-Indigenous citizens do. Even if they are granted observer status, the cities members to the AMF will have a more limited means than permanent participants to influence policy-making in the Arctic Council.

For the discussion of legitimacy in inter- and transnational cooperation, the example of the AMF is telling for three reasons. First, it shows that cities alliances are special kinds of non-state actors that are likely to obtain greater legitimacy than other non-state actors if their representatives are elected. Yet, the activities of transnational cities alliances are not driven by public mandates or state policies. Instead, they result from the negotiations among the cities that are members to it, even though the mayors engaged may push positions in accordance with national policies and in consideration of electoral cycles. Cities alliances are thus embedded “within a number of political dynamics that have important bearing on whether and to what extent they will make a difference” (Gordon & Johnson, 2018, p. 37).

Second, the Arctic municipalities engaged in the AMF exemplify the different means they have to influence policy-making at the regional and global levels. These means are determined by their individual capacities and capabilities and also by national governments. To contribute to policy-making at the regional and global levels, municipal leaders either use their channels via the national government or participate in alliances across borders, such as the AMF. This unformalised and unstructured process privileges municipal leaders with good networks and the capacities to prepare for, travel to and engage in meetings far from their municipalities. As the development of the AMF also illustrates, smaller cities are more likely to be left behind (Wehrmann et al., 2022), limiting the representativeness and legitimacy of the forum.

Third, for Arctic municipalities – with a public mandate to represent Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens in the Arctic regions – membership to transnational cities alliances seems promising in helping to “make the voices [of their citizens] heard” across governance levels. Also, the growing number of cities alliances worldwide mirrors this expectation of gaining visibility and influence when participating in these networks. However, the case of the AMF exemplifies that – even in regions shaped by long-lasting and multiple forms of inter- and transnational cooperation – having local perspectives systematically considered in regional and global policy-making is not a given. Even if the Arctic Council resumes its operations and the AMF is granted observer status, it is very likely that the AMF – similar to most other observers in the Arctic Council – will not be able to make significant contributions to the work being conducted by the Council. In order to represent the citizens of the Arctic municipalities that are members of the AMF in all working groups, the Arctic Council would have to adapt its institutional design and support the inclusion of non-state actors by empowering them with mechanisms that consider the different capacities and capabilities of non-state actors.

Conclusion

There is broad acceptance that a more representative inclusion of non-governmental actors and more transnational exchanges are needed to develop more holistic approaches in policy-making (Horner & Hulme, 2017), and that they can also contribute to the effectiveness of international organisations (Sommerer, Squatrito, Tallberg, & Lundgren, 2021). Yet, this broad acceptance – which also guides the intentions for reform expressed by the UN Secretary-General in the “Our Common Agenda” report – does not translate smoothly into efforts to modify existing institutions, as the debate on how to organise and implement the reform of the UN shows. Interestingly, although the rifts between those states that favour the participation of transnational actors in decision-making and those that seek to preserve intergovernmental prerogatives will shape the future of UN reform to a great degree, transnational actors themselves also hold different viewpoints on how their access should be guaranteed and regulated. These differences among transnational actors become even more important in the second case that we analysed. Cities alliances have become as “important as transnational actors in global governance” (WBGU, 2016, p. 106). For international organisations aiming to advance and coordinate their collaboration with transnational actors such as cities alliances, the case of the AMF shows that cities alliances need to be treated similarly to multi-actor partnerships. Even though they are not composed of different types of actors, the cities engaged in alliances have different means to influence policy-making and follow different interests. ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples illustrate that international agreements have a great potential to legitimise (transnational) non-state actors in policy-making. The case of transnational cities alliances such as the AMF shows, however, that any international agreement envisioned to strengthen the introduction of local perspectives to global policy-making runs the risk of privileging particularly the capacity-strong members that are already shaping transnational networks as well as national and global policy-making. To provide a greater say for local perspectives, which are still often left unconsidered, it thus seems to be useful for international organisations to not only facilitate their participation, but also to seek real contributions in policy-making processes.

References

Albert, M., Bluhm, G., Helmig, J., Leutzsch, A., & Walter, J. (Eds.) (2009). Transnational political spaces: Agents – structures – encounters. The University Press of Chicago, Campus Verlag.

Arctic Mayors’ Forum. (2022). About the forum. https://arcticmayors.com/about-the-forum/

Beisheim, M. (2021). Conflicts in UN reform negotiations. Insights into and from the review of the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (SWP Research Paper 2021/RP 09). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

Beisheim, M., & Simon, N. (2018). Multistakeholder partnerships for the SDGs: Actors’ views on UN meta governance. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 24(4), 497-515. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02404003

Chaturvedi, S., Janus, H., Klingebiel, S., Li, X., Mello e Souza, A. D., Sidiropoulos, E., & Wehrmann, D. (2021). The Palgrave handbook of development cooperation for achieving the 2030 Agenda: Contested collaboration (p. 730). Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-57938-8

Civil Society Financing for Development Group. (2022). Civil society Financing for Development (FfD) group response to SG’s “Our Common Agenda” report. https://csoforffd.files.wordpress.com/2022/02/csffd-response-feb9-1.pdf

Dingwerth, K., Witt, A., Lehmann, I., Reichel, E., & Weise, T. (Eds.) (2019). International organizations under pressure: Legitimating global governance in challenging times. Oxford University Press.

Falkner, R., Nasiritousi, N., & Reischl, G. (2021). Climate clubs: Politically feasible and desirable? Climate Policy, 22(4), 480-487. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14693062.2021.1967717

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2022). FAO strategy on climate change 2022–2031. Author.

Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. (2022). Private-sector engagement. https://www.effectivecooperation.org/landing-page/action-area-21-private-sector-engagement-pse

Gordon, D. J., & Johnson, C. A. (2018). City-networks, global climate governance, and the road to 1.5 °C. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 30, 35-41.

Government of Canada. (2022). Declaration on the establishment of the Arctic Council. https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/arctic-arctique/declaration_ac-declaration_ca.aspx?lang=eng

G7 Germany. (2022a). G7 to set up Climate Club. https://www.g7germany.de/g7-en/news/g7-articles/g7-climate-club-2058310

G7 Germany. (2022b). G7 statement on Climate Club. https://www.g7germany.de/resource/blob/974430/2057926/2a7cd9f10213a481924492942dd660a1/2022-06-28-g7-climate-club-data.pdf?download=1

Horner, R., & Hulme, D. (2017). From international to global development: New geographies of 21st century development. Development and Change, 50(2), 347-378.

Johnson, C., Dowd, T. J., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Legitimacy as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 53-78.

Kankaanpää, P., & Young, O. R. (2012). The effectiveness of the Arctic Council. Polar Research, 31(1), 17176. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269829323_The_effectiveness_of_the_Arctic_Council

Knecht, S. (2020). The Arctic Council, Asian observers and the role of shadow networks in the science-policy interface. In C. Y. Woon & K. Dodds (Eds.), “Observing” the Arctic: Asia in the Arctic Council and beyond (pp. 29-53). Edward Elgar.

Kuramochi, T., Lui, S., Höhne, N., Smit, S., Casas, M. J. d. V., Hans, F., & Hale, T. (2019). Global climate action from cities, regions and businesses: Impact of individual actors and cooperative initiatives on global and national emissions. New Climate Institute. https://newclimate.org/2019/09/18/global-climate-action-from-cities-regions-and-businesses-2019/

Mawdsley, E. (2021). Development finance and the 2030 goals. In S. Chaturvedi, H. Janus, S. Klingebiel, X. Li, A. De Mello e Souza, E. Sidiropoulos, & D. Wehrmann (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of development cooperation for achieving the 2030 Agenda (pp. 51-57). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-57938-8_3

Pipa, A. F., & Bouchet, M. (2020). Multilateralism restored? City diplomacy in the COVID-19 era. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 15, 599-610.

President of the UN General Assembly. (2022). Our Common Agenda: Summary of thematic consultations. https://www.un.org/pga/76/2022/05/20/letter-from-the-president-of-the-general-assembly-final-oca-summary/

Pries, L. (2010). Transnationalisierung. Theorie und Empirie grenzüberschreitender Vergesellschaftung. Springer VS.

Schnappauf, W., Scholz, I., Bassen, A., Burchardt, U., Dubourg, S., Füllkrug-Weitzel, C. …Weinlich, S. (2022). Our Common Agenda – impetus for an inclusive and networked multilateralism for sustainable development. Statement. Rat für Nachhaltige Entwicklung. https://www.nachhaltigkeitsrat.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/20220120_RNE-Statement_Our-Common-Agenda-Guterres_EN.pdf

Sommerer, T., Squatrito, T., Tallberg, J., & Lundgren, M. (2021). Decision-making in international organizations: Institutional design and performance. The Review of International Organizations, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09445-x

Steffek, J. (2003). The legitimation of international governance: A discourse approach. European Journal of International Relations, 9(2), 249-275.

Tallberg, J., & Zürn, M. (2019). The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: Introduction and framework. Review of International Organisations, 14, 581-606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7

United Nations. (2021). Our Common Agenda – report of the Secretary-General. https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2021). Major groups and other stakeholders: A review and evaluation of the engagement in the 2020 and 2021 sessions of the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) and areas to strengthen participation in 2022. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/29458MGoS_ReviewEvaluation_of_Engagement_20202021_HLPF.pdf

US Department of State. (2022). Joint statement on limited resumption of Arctic Council cooperation. https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-limited-resumption-of-arctic-council-cooperation/

Voosen, P. (2021). The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/arctic-warming-four-times-faster-rest-world

WBGU (German Advisory Council on Global Change). (2016). Humanity on the move: Unlocking the transformative power of cities. https://www.wbgu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/wbgu/publikationen/hauptgutachten/hg2016/pdf/hg2016_en.pdf

Wehrmann, D. (2018). Incentivising and regulating multi-actor partnerships and private-sector engagement in development cooperation (DIE Discussion Paper 21/2018). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). https://doi.org/10.23661/dp21.2018

Wehrmann, D., Łuszczuk, M., Radzik-Maruszak, K., Riedel, A., & Götze, J. (2022). Transnational cities alliances and their role in policy-making in sustainable urban development in the European Arctic. In N. Sellheim & D. R. Menezes (Eds.), Non-state actors in the Arctic Region (pp. 113-131). Springer International Publishing.

World Bank. (2022). Fragility, conflict & violence. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/overview

The involvement of the private sector and other non-state actors in EU development policy: current ambitions and directions

Julian Bergmann, Benedikt Erforth & Niels Keijzer

Abstract

The European Union (EU) is a unique cooperation actor that, together with its 27 member states, is the largest provider of official development assistance (ODA). This contribution describes the overall place and role of the EU and discusses two specific trends that reflect its current approach to respond to global challenges: a strong focus on promoting external investment in cooperation with the private sector, and a focus on multi-stakeholder approaches, the latter with a focus on conflict prevention and peacebuilding activities. Taken together, the two trends represent a stronger focus on transnational cooperation with, and through, non-state actors. Such a shift requires important investments on the part of the EU to understand business climates, investment as well as a more networked understanding of both local and international civil society organisations (CSOs). Although the EU is well-placed to navigate the transitions that are required, this transnational approach may also entail a reduced role for the state or sub-national actors, which, in turn, comes with additional costs – and might even have negative effects on specific stakeholder groups. Particularly in the case of cooperation in non-conducive and fragile contexts, the EU needs to adequately invest in continuous monitoring and evaluation processes that reflect its willingness to learn from both success and failure.

Introduction

The EU is neither a state, nor an intergovernmental organisation. Its progressive and ongoing process of broadening and deepening integration – with the concept of “subsidiarity” capturing the overall idea that member states willingly transfer policy competence to the EU level for collective and mutual benefit – makes the EU a unique actor in transnational cooperation. To achieve the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which build on the aspiration of wanting to strengthen the world’s common good, it requires well-functioning transnational cooperation partnerships. Such well-functioning partnerships, as Grimm and Klingebiel (see introduction) point out, must be multi-stakeholder in nature. The EU itself – being a supranational organisation “sui generis” – contains multi-stakeholder, transnational platforms within its institutional DNA and is therefore well-placed to advance a global transnational cooperation agenda.

While the EU avails of “common policies” in areas including trade and agriculture policy, in the field of development policy, EU institutions and its member states maintain parallel competences. Under this arrangement, the member states mandate and empower the EU as a distinct actor that – according to the EU Treaty – complements the development policy operations of the member states, and vice versa. This institutional skill set is applied to a manifold of geographic and sectoral engagements, two of which are analysed in this contribution.

The EU operates with a seven-year budget cycle known as its Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF). Under the current MFF, the most relevant budgetary instruments for international cooperation include the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI, also referred to as “Global Europe instrument”) with a budget of EUR 79.5 billion for the period 2021-2027 (see Burni, Erforth, & Keijzer, 2021). As per its legal basis, at least 93 per cent of that total budget “[…] should contribute to actions designed in such a way that they fulfil the criteria for ODA”, that is, a minimum of EUR 73.9 billion (European Union, 2021, preamble 21). In addition to the NDICI, the EU avails itself of the Instrument of Pre-Accession, which supports reforms in the so-called enlargement region with financial and technical assistance at a total budget of EUR 14.2 billion for the current MFF, and the intergovernmental European Peace Facility with an initial EUR 5.7 billion budget to support peace operations outside the EU’s borders during the same period. The budget of the European Peace Facility has meanwhile more than doubled as a result of the central role it plays in the EU’s response to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine (European Commission, s.a.).

The EU’s considerable international cooperation budget surpasses the individual bilateral development cooperation resources of its member states, with Germany being the sole exception; see the preliminary ODA statistics for 2021 (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021). This considerable budget will be used for grant-based financing and includes an earmarked budget of EUR 1.4 billion for support to CSOs, which in addition are also eligible to implement relevant projects under the instrument’s geographic and thematic strategies. The available financial resources under the instrument are also used in the form of “blended finance” to leverage and guarantee public and private investment in developing countries. Both aspects – the involvement of CSOs and the use of public finance to stimulate private investments – lend themselves as exploratory cases to further delve into the question of how well the EU can perform in a world where the ability to effectively engage in transnational cooperation has become key to success and – maybe even – survival.

It should be noted that the features of the EU’s current international cooperation framework represent a relatively recent and rather fundamental departure from the EU’s past approach and emphasis. Although the support to CSOs was an early feature of the EU’s development cooperation when it started in 1979 (Keijzer & Bossuyt, 2020), such support continued with a relatively low-profile and at a limited scale compared to the dominant focus on direct cooperation with third-country governments. Past development policy debates emphasised the EU’s ability to predictably provide grant-based financing over longer periods of time, and the EU was known for its investments into public infrastructure (also linked to “aid for trade”) as well as its provision of budget support (Bergmann, Delputte, Keijzer, & Verschaeve, 2019).

This predominant “statist” and grant-based cooperation focus particularly changed following the advent of the global financial and economic crisis in September 2008. It has been expressed as two main shifts, which we briefly introduce here and then explore further in turn. The first shift considers a stronger focus on the productive sector and the investment promotion of both public and private actors. After having provided short-term-oriented fiscal support, in 2011 the EU adopted new development policy preferences with a stronger focus on the private sector (Bergmann et al., 2019). Today, this has evolved into the mobilisation of investment being among the key priorities of the EU’s development policy, backed by its conviction that public finance alone can never be sufficient to realise the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as well as its very own liberal identity, which values the power and positive impact of entrepreneurship and private capital.

A second important shift concerns the EU’s efforts to diversify its international partnerships. These partnerships, such as the well-known partnership agreement with the African, Caribbean and Pacific states and the various bilateral association agreements, typically are agreed with states, as these are the only ones legally able to enter into international agreements. The agreements themselves and the dialogue structures around them, however, increasingly emphasise and promote the participation of non-state actors, with the EU being a pioneering actor in terms of introducing such dialogue structures in the 1970s. The increasing focus on working with non-state actors – either directly or qua intermediaries such as public development banks – goes beyond development policy in a strict sense, as it has also become more prominent in the EU’s support to conflict prevention and peacebuilding.

Using EU ODA to mobilise private investment for “hard to invest” places

Climate change, migration, poverty conflicts and demographic challenges are steady preoccupations of decision-makers in Brussels and beyond (European Commission, 2018). These developments coincide with a continuous stagnation in ODA budgets over the past years, showing the limits of what public funds can achieve in an unstable world. Together – and in light of the annual investment gap for development of USD 2.5 trillion – these factors have induced a fundamental shift in the way development cooperation is framed today. The adoption of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in 2015 institutionalised the popular narrative of private-sector solutions for sustainable development. The signatories agreed that private-sector investments are to compensate for the lack of public funds necessary to achieve the SDGs. To incentivise private-sector investments, national, international and supranational actors alike rely on an increasingly complex web of financial instruments that are aimed at mitigating private risks and creating an environment conducive to sustainable investments, innovation and entrepreneurship.

By shifting investors’ perceptions of “risks versus potential returns, blending is viewed as a means of tapping into new resources” (Lundsgaarde, 2017, p. 5). Next to its promise to leverage additional investments with a limited amount of public funds, blending is also cherished for improving the quality of financed projects by allowing for a knowledge exchange between development actors and investors. In addition, blending may further the coordination between large bilateral and multilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) and EU institutions (Lundsgaarde, 2017). Greater coherence among European DFIs, in turn, is hoped to increase the visibility of European action abroad (Erforth, 2020). In particular, in light of China and other external actors’ rising – and rivalling – activism and its growing investments in Africa, the EU is inclined to view a coherent development finance system as part of a broader toolbox to support sustainable development in Africa and defend European stewardship in the international system. This element of geopolitical competition was also emphasised in the EU’s 2021 Global Gateway proposal to ramp up global infrastructure investments (Furness & Keijzer, 2022). This last point is interesting, insofar as the activation of non-state actors serves the purpose of strengthening (state) sovereignty.

The EU’s increased attention on the private sector is in line with a general shift in the global development finance landscape. Accordingly, the role of DFIs has been strengthened, as their lending volume has increased. Today, development banks create an ever-greater number of financial instruments that in one way or another serve as guarantees or securities to potential private investors. In theory, this approach is well-suited to mobilise additional finance and overcome old dependencies. In practice, however, it has also resulted in shifting the attention from least-developed and fragile states to middle-income countries, where the impact of public guarantees and the likelihood of such guarantees helping to generate bankable projects that will attract investors are reckoned to be greater. The shift away from international to transnational cooperation, hence, might be detrimental to the world’s poorest countries and effectively undermine the poverty eradication agenda (Attridge, 2019).

The focus on blending and private-sector support, paired with its criticism, begs two sets of questions: i) What impact and/or leveraging effects do blending mechanisms have? And ii) What is or ought to be the role of the state and public institutions in the area of development finance? Critics maintain that existing blending operations do not come close to reaching the promised leveraging effect, pointing to trade-offs between blending and other “development-oriented interventions that could have been funded with the same resources” (Lundsgaarde, 2017, p. 11).

To successfully contribute to the changing nature of development cooperation, the EU needs to find the right balance between the various instruments available and engage in context-specific measures. For the former, a more advanced evaluation of blending mechanisms and the achieved results is necessary. For the latter, concessional loans and guarantees must stand the test of generating both financial and developmental additionality within the contexts they are applied to (see also Furness & Keijzer, 2022). An outright rejection of new forms of public–private transnational cooperation partnerships is not an option – due to the above-mentioned financing gap as well as the necessity to think and act “beyond aid”.

In sum, transnational cooperation partnerships between a multitude of private and public stakeholders are a necessity in the area of financial cooperation. Better frameworks that serve as a measuring threshold need to be put in place. These can only be developed together with partner countries and/or partner organisations, which makes the assessment itself a form of transnational cooperation. The same is true for the second requirement, which asks European development finance to identify the right instruments that speak to the economic, social and political differences between and within countries. Only by listening to the existing variety of voices can this exercise succeed.

Europe’s cooperation with CSOs in conflict prevention and peacebuilding

A significant share of EU activities targeting conflict-affected countries and their populations draws on intermediary actors to prevent and resolve conflict and build peace. Many of those intermediary actors are CSOs. Before the creation of the NDICI/Global Europe instrument in 2021, the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP) had been the EU’s main financial instrument to fund support in the fields of crisis response, conflict prevention and peacebuilding, with a financial envelope of EUR 2.3 billion for the period between 2014 and 2020.

Through the IcSP, the EU funded a wide array of conflict prevention and peacebuilding-related activities, ranging from mediation and dialogue, security-sector reform, transitional justice, support to the implementation of the UN Women, Peace and Security Agenda (WPS), demining actions and counter-terrorism activities.

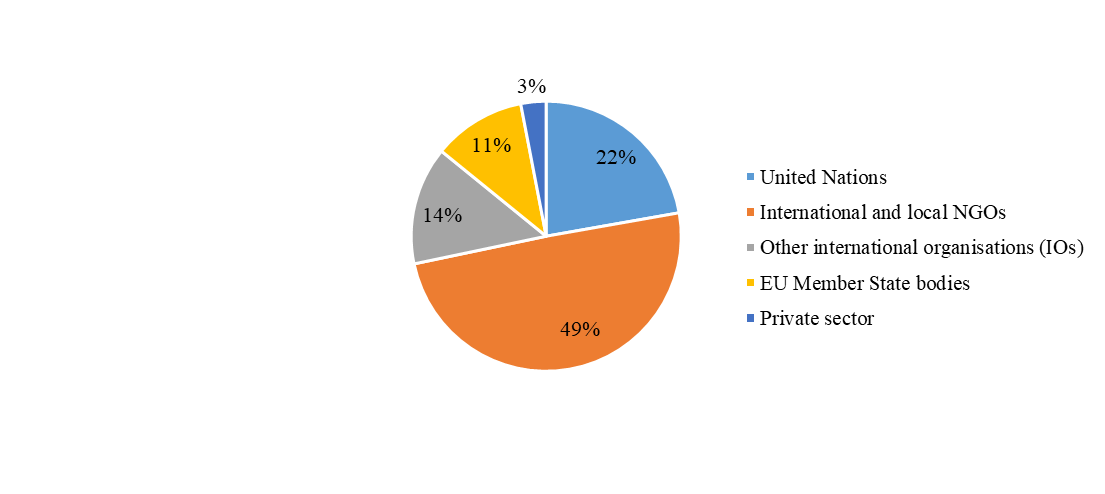

According to an analysis of 268 IcSP projects between 2014 and 2017, almost half of them were implemented by international and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (49 per cent), followed by UN organisations (22 per cent), other international organisations (14 per cent), EU member state bodies and agencies (11 per cent) and the private sector (3 per cent). Focussing on partners that implemented the largest share of IcSP funding, UN organisations come out top (32 per cent), closely followed by international and local CSOs (31 per cent), other international organisations (19 per cent), EU member state bodies and agencies (15 per cent) and the private sector (4 per cent) (Bergmann, 2018, pp. 15-16; see Figure 1). In other words, non-state actors (international organisations, CSOs, private sector) are the largest group among the implementing agents of IcSP projects, and within this group, CSOs stand out as the most frequent cooperation partners of the EU.

Figure 1: Distribution of IcSP projects per implementing partner

Source: Bergmann (2018, p. 16)

Zooming onto the group of international and local CSOs as implementation partners in 130 out of 268 projects, we find a wide variety of organisations in terms of the specific focus of their activities and their geographical scope. A local civil society actor such as the Conférence Episcopale Nationale du Congo, which focusses on one particular conflict, and an internationally operating NGO such as International Alert are just two examples of a wide continuum of various types of organisations that have received EU funding through the IcSP. Whereas most actors only implemented one to a maximum of two projects within the investigation period, four international CSOs stand out as the most frequent implementers: The Centre Henry Dunant pour le Dialogue Humanitaire (7 projects), the Danish Refugee Council (6), Search for Common Ground (5) and International Alert (5).

Apart from projects implemented by individual CSOs, the IcSP also funded larger consortiums consisting of several organisations to carry out specific tasks, thus facilitating transnational cooperation between several non-state actors. One example in this regard is the European Resources for Mediation Support (ERMES) project, which facilitates EU support to third parties engaged in mediation and dialogue processes. In its third project phase from 2018 to 2024, it has been implemented by a consortium under the leadership of the College of Europe. It involves specialised organisations and institutes such as the European Forum for International Mediation and Dialogue (mediatEUr); Interpeace; the European Centre for Electoral Support; Fondation Hirondelle; and the Institute of Research and Education on Negotiation (ESSEC-IRENE). The consortium established a pool of mediation experts who can be deployed to conflict situations on very short notice if the EU mandates them to do so. Through ERMES, the EU is able to deliver support to peace processes within 48 hours after the emergence of a crisis. Interestingly, ERMES support can be requested by any EU foreign policy body, including EU delegations, the European External Action Service, the Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation, and EU Special Representatives and Envoys (College of Europe, 2019). The example of ERMES shows that the EU is not only interacting with NGOs and/or CSOs on a bilateral basis, but also funds larger consortia of various organisations. Thus it “orchestrates” NGO-NGO collaboration through EU funding mechanisms, which provide collective resources that can, in turn, again be utilised by EU institutions.

In sum, this brief empirical overview of the EU’s cooperation practices indeed shows that transnational cooperation, that is, cross-border interaction beyond public national actors, is at the heart of the EU’s approach to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. The benefit of the EU’s transnational cooperation with local and international NGOs and CSOs in situations of fragility and conflict-affected countries – which often takes place in parallel to interaction with state actors – lies in the unique resources that these actors possess and that can be leveraged through transnational cooperation with the EU. Local CSOs often have preferential access to conflict zones and parties, and they possess rich knowledge of the dynamics “on the ground”. In situations where cooperation with governments or other national public actors in conflict-affected countries might be difficult or stalled, transnational cooperation has the potential to open new pathways for conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts beyond traditional state-to-state diplomacy.

Moreover, transnational cooperation allows the EU to become engaged in conflict theatres – and with conflict parties – where it does not want to become officially recognised for its direct engagement. For example, when interacting with proscribed non-state armed groups or terrorist organisations (such as Hamas or the Houthi in Yemen), the EU often engages with and through local and international NGOs and CSOs, which then establish interactions with those groups and organisations (Müller & Cornago, 2019). Finally, transnational cooperation for conflict prevention and peacebuilding in conflict-affected countries strengthens the legitimacy of the EU as an international actor and as a force for the global common good because it acknowledges that sustainable peace can only be built through multi-stakeholder approaches that involve non-state actors at all levels of society.

Conclusion: trends and learning needs

The EU is both well-endowed and well-placed to facilitate transnational cooperation, but it faces the challenge of effectively allocating resources to a growing number of global challenges. Two trends reflect its current approach to addressing such challenges effectively: a strong focus on promoting external investment in cooperation with the private sector, and a focus on multi-stakeholder approaches, the latter with a focus on conflict prevention and peacebuilding activities.

The greater focus on non-state actors in today’s EU international cooperation – both as an aim in itself and as a “channel” for project delivery – requires important investments on the part of the EU to understand business climates, investment as well as a more networked understanding of both local and international CSOs. The two trends suggest that the EU is well-positioned to navigate the present-day global system, in which cooperation is no longer international, but transnational. Yet, we can also see that a reduced role for the state or sub-national actors sometimes comes with additional costs and might even have negative effects on specific stakeholder groups. Rather than reject the new nature of cooperation, the EU needs to make sure that these negative impacts are mitigated by public policy.

As part of the ongoing “Team Europe” efforts to promote joint action between the EU and its member states, all actors involved should engage in further knowledge-sharing and direct cooperation on realising such ambitious cooperation programmes with the limited human resources they have available. Moreover, in order to successfully mitigate any associated risks – especially in the ambitious field of promoting external investment in non-conducive investment climates – adequate investments in continuous monitoring and evaluation processes are needed. They would reflect the openness of the EU to learn from both success and failure.

References

Attridge, S. (2019). Blended finance in the poorest countries: The need for a better approach (ODI Report). https://odi.org/en/publications/blended-finance-in-the-poorest-countries-the-need-for-a-better-approach/

Bergmann, J. (2018). A bridge over troubled water? The Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP) and the security-development nexus in EU external policy (DIE Discussion Paper 6/2018). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Bergmann, J., Delputte, S., Keijzer, N., & Verschaeve, J. (2019). The evolution of the EU’s development policy: Turning full circle. European Foreign Affairs Review, 24(4), 533-554.

Burni, A., Erforth, B., & Keijzer, N. (2021). Global Europe? The new EU external action instrument and the European Parliament. Global Affairs, 7(4), 471-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2021.1993081

College of Europe. (2019). ERMES III – European Resources for Mediation Support. https://www.coleurope.eu/training-projects/projects/projects-spotlight/ermes-iii-european-resources-mediation-support

Erforth, B. (2020). The future of European development banking: What role and place for the European Investment Bank? (DIE Discussion Paper 11/2020). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

European Commission. (2018). Towards a more efficient financial architecture for investment outside the European Union (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council and the European Investment Bank) (COM(2018) 644 final). Author.

European Commission. (s.a.). European Peace Facility. https://fpi.ec.europa.eu/what-we-do/european-peace-facility_en

European Union. (2021). Regulation (EU) 2021/947 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 June 2021 establishing the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument – Global Europe. Author.

Furness, M., & Keijzer, N. (2022). Europe’s Global Gateway: A new geostrategic framework for development policy? (DIE Briefing Paper). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). https://doi.org/10.23661/bp1.2022

Keijzer, N., & Bossuyt, F. (2020). Partnership on paper, pragmatism on the ground: The European Union’s engagement with civil society organisations. Development in Practice, 30(6), 784-794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1801589

Lundsgaarde, E. (2017). The European Fund for Sustainable Development: Changing the game? (DIE Discussion Paper 29/2017). German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Müller, P., & Cornago, N. (2018). Building peace through proxy-mediation: The European Union’s mediation support in the Libya conflict (Working Paper 1/2018). Institute for European Integration Research.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). ODA levels in 2021 – preliminary data. https://web-archive.oecd.org/2022-04-12/629684-ODA-2021-summary.pdf

Transnational cooperation and social contracts

Mark Furness

Abstract