©shutterstock_180430298

©shutterstock_180430298

In times of a global rise of right-wing populism, multilateral cooperation is under attack and with that international agreements. Against this backdrop, it might be fruitful to have a closer look at the success factors behind multilateral cooperation and assess whether they could also work vis-à-vis populist governments, especially with regard to the Paris climate negotiations.

Multilateral cooperation is currently under attack by a global rise of right-wing populism. Major economies like the USA, Brazil or India are led by rightist populist leaders and also within the EU, populist parties are growing faster than ever since the end of WWII.

Prospects for multilateral cooperation are thus dim. The list of setbacks to multilateral institutions driven by right-wing populists in recent years is already long: The US announcement to withdraw from the Paris Agreement (2017) and the UN Human Rights Council (2018), a lack of approval for the Global Compact for Migration by Hungary, Poland and the US (2019), the breakdown of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty (2019) and the escalating US-China trade war regardless of WTO standards (2019) are some of the major examples. The G7 are also affected by this downward trend – the summits in Italy 2017 and Canada 2018 revealed major fault lines especially between US-president Donald Trump and the rest of the group.

Yet, the latest G7 summit in Biarritz in 2019 also provided some positive news (progress on Iran and global digital tax, emergency funds for the Amazon, Partnership on Gender Equality) and indicated that skilful diplomacy can contribute to moderate successes despite having populists at the negotiation table. Against this backdrop, it might be fruitful to have a closer look at the success factors behind multilateral cooperation and assess whether they could also work vis-à-vis populist governments.

Factors for cooperation: Evidence from climate negotiations

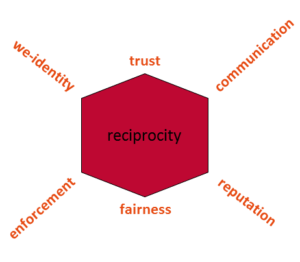

While dominant theories in international relations, such as neorealism, currently make us expect little for international cooperation, other scientific disciplines stipulate a principal human ability to cooperate. A vast body of research of various disciplines from behavioural economics to social psychology has found a surprising consistence on the factors that enable human cooperation in the face collective action problems like public-good dilemmas and common-pool resource problems when individuals in small groups interact. Communication, trust, reputation, fairness, enforcement, we-identity and reciprocity drive cooperation between people, and form a Cooperation Hexagon (see diagram).

Communication, trust, reputation, fairness, enforcement, we-identity and reciprocity drive cooperation between people, and form a Cooperation Hexagon (see diagram).

However, it has not yet been sufficiently examined whether these insights can be transferred to the multi-dimensional discipline of international relations in which not only individuals but complex entities such as nation states interact. First empirical evidence suggests that some of these factors are indeed crucial at the international level. Let’s take climate negotiations as a case to study. Climate change constitutes a global-scale collective action problem. Can the failure or success of high-level climate summits like in Copenhagen in 2009 (COP 15) and Paris in 2015 (COP 21) be explained by an (under-)provision of cooperation factors? First of all, there is no one-dimensional answer to this: Climate negotiations are complex phenomena shaped by many exogenous factors, such as the commitment of heads of state towards green policy or the cost of climate-friendly technologies. Nevertheless, a climate agreement in Paris would not have been possible without a change in the enabling factors for cooperation.

The major changes between COP 15 and COP 21 took place in the realms of communication, trust, and enforcement as well as fairness and reputation. Each round of climate negotiations is facilitated by a presidency, whose task is to organise the negotiations, stimulate dialogue, create common ground and, finally, propose an agreement. A first observation is the importance of the performance of the presidency in communication and trust-building. During COP 15 in Copenhagen, it transpired that the Danish presidency engaged in in secret bilateral negotiations, side-lining the multilateral process of the UNFCCC. Trust was damaged, as negotiations were perceived as being non-transparent and exclusive. In contrast, the French presidency during COP 21 built trust by launching an unprecedented round of climate diplomacy in the run-up. Emphasis was put on cultivating a manner of listening to all parties equally and communicating transparently.

A second observation is the interconnection of the level of enforcement and fairness debates. An envisaged “global deal” resulted in distributional conflicts and a deep political division between developed and developing countries during COP 15 over legally binding emission-reduction obligations. As this so-called “top-down” model aimed at the establishment of an enforcement mechanism, this ran counter to the notion of national sovereignty brought forward by some countries. The BASIC country group (China, India, Brazil, South Africa) were particular important proponents of national sovereignty. COP 21 “resolved” the issue by lowering the envisaged level of enforcement. The allowance for self-differentiation based on “nationally determined contributions” resolved impeding fairness debates and enhanced participation. This, at least, allowed for agreeing on a basis; one that can and needs to be worked on.

Reputation as a factor for cooperation was lacking during the Copenhagen conference, as developed and developing countries shifted the blame mutually. However, it became a factor during the Paris conference as this division crumbled, meaning that ambitious countries could address non-cooperative countries’ reputational concerns in order to encourage their cooperation.

And multilateral cooperation in times of populism?

Some of the cooperation factors are less likely to work when right-wing populist leaders are involved. International reputational concerns seem to hardly play any role for the behaviour and decision making of the likes of US-president Trump. Little prospects for the evolvement of global we-identities exist when identities are firmly set at national level only.

Lessons might be elsewhere, though. One interesting observation from the climate negotiation process is the lowering of the envisaged level of enforcement of the regime which increased participation and settled distributional conflicts. For right-wing populists, notions of national sovereignty are even more sensitive and the willingness to transfer authority to an international regime is particularly low. Therefore, it makes sense to refrain from aiming to negotiate ambitious international regimes but keep the process as open-ended as possible. The G7 summit in Biarritz in which the French presidency ceased from providing a pre-agreed final communiqué is an example for this and might have helped to build trust.

Moreover, international relations with populist leaders are becoming more personalized. Personal relations and informal communication are therefore growing in importance, including in trust building. Last but not least, the example of political behaviour in the Amazon, where an indifferent Brazilian president Bolsonaro became more responsive in environmental protection after some EU countries threatened to withdraw from the Mercosur trade agreement, indicates that the EU’s usage of its economic weight to stimulate cooperation on environmental policy could be a successful enforcement strategy. Dealing with populists in government is not an easy thing to do but considering the little time the international community has left to keep climate change below 2°C, there is no way around it. To think of strategies on how to engage right-wing populists in this matter is therefore not a betrayal of liberal values but a pragmatic necessity.

Schreibe einen Kommentar