Advanced economies hold China responsible for global steel overcapacity. Yet, the postwar era has witnessed two steel overcapacity crises. The current debate cannot ignore past lessons.

Before the 2016 G20 Summit in Hangzhou, then-President Obama was urged by US lawmakers, unions and trade associations to address China’s steel overcapacity. He was seconded in this endeavour by the EC president Jean-Claude Juncker, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his Canadian counterpart Justin Trudeau. However, while the G20’s spotlight in the steel overcapacity crisis has focused on China, the nature of the crisis and associated disputes about its causes cannot be so neatly attributed to the actions of any single country.

In China, steel output climbed to the highest level on record last March, with faster-than-anticipated growth in the first quarter having been fueled by the use of steel in the construction sector. In the US, President Trump’s “Buy American, Hire American” executive order may not have the intended impact on the consumption of U.S. steel. However, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross has announced an investigation to determine whether Chinese and other foreign-made steel is a threat to U.S. national security, possibly laying the groundwork for future tariff action.

While steel output in India has been forecast to more than double by 2031, industry behemoth Tata Steel hopes to write a cheque for $663 million to clear its liabilities to UK pensioners in a once-off settlement that reflects Tata’s plans to support future group consolidation. The effort is concurrent with Tata’s proposed merger with Thyssenkrupp’s steel operations, which German trade unions have threatened to derail amid similarly complex negotiations relating to the future of their pension plans.

Japan, meanwhile, has alleged that duties imposed on steel imports by India violate trade norms of the World Trade Organization. As the 19th Global Trade Alert Report concluded, “protectionism in [the steel] sector has been ratcheting up since 2010.”

Amid such challenging dynamics in the global steel industry, it is worth remembering that this is not the first time the industry has faced an overcapacity crisis.

Steel overcapacity crises in the 1970s and today

Although the G7 nations‘ focus remains on China’s steel overcapacity, consider the following quote: “Recent years… have been very difficult ones for the steel industries of the United States and Europe. Production in both regions has dropped by more than one-third and employment has fallen even more. In recent years there have been either large losses or small profits.”

While these sentiments echo those of China’s contemporary G7 critics, they were in fact expressed by David Tarr, a senior economist with the US Federal Trade Commission, who in 1988 was examining the then-steel crisis in the US and Europe.

Since the postwar era, crude steel production has passed through three phases. Prior to the mid-70s, global steel production grew an impressive 5% per year. This was driven by Europe’s reconstruction and industrialization, and catch-up growth in Japan and the Soviet Union.

In the 1970s, this boom period ended in two global energy crises, after which stagnation ensued and global steel demand barely ticked above 1.1% per year. In the US, challenges confronting the Rustbelt led to labor turmoil and offshoring, giving way to the Reagan era. In the UK, similar turmoil paved the way to the Thatcher years.

The third phase took place between 2000 and 2014, with China’s industrialization leading to a massive expansion in steel production and demand, fueling annual growth by 13%. In the past two decades, total world crude steel production has more than doubled to 1,670 million tons. Today, China accounts for almost half of the worldwide total – as the US did in 1950.

While China’s industrialization and urbanization may continue for another 10-15 years, its most intensive phase of expansion is now behind it. As a result, the steel sector is facing an expected period of overcapacity and stagnation for 5-15 years.

Policy responses in the 1980s and today

In early 2016, the European Chamber of Commerce in China released a report about Chinese steel overcapacity, which included a section on the “history of overcapacity.“ It urged Beijing to take stock of the late 1990s, when Premier Zhu Rongji shut down state-owned enterprises, which left 40 million workers redundant. But could Zhu’s tough medicine work in contemporary China?

When Zhu began his stabilization program in the mid-90s, only 30% of China’s population was urbanized , such that there was great potential for industrialization, export-led expansion and catch-up growth. Advanced economies were also not yet mired in secular stagnation. Between 1995 and 2015, China shifted over 300 million people from rural areas into cities. By 2050, China may move another 290 million people into urban areas. But the previous factors that enabled double-digit catch-up growth are no longer in abundance.

Given this shift in circumstances in China, it is worth considering whether the US and Europe implemented the kind of defaults in production during the previous steel crisis that they now advocate for China. The short answer is no. Instead, the open postwar trading regime took a backwards step as more aggressive trade practices arose both in the US and Europe. As both Washington and Brussels sought to protect their markets through non-tariff barriers, they embraced protectionist external policies. That being said, US policymakers avoided direct intervention in the domestic market and allowed domestic firms to suffer large losses, resulting in huge plant closures. In contrast, Brussels initially imposed production quotas and minimum prices; later, it sought to restrain subsidies and investment, while reducing capacity.

Today, China’s steel sector plans to shrink capacity by 100-150 million metric tons over the next five years. If current overcapacity is reduced by 30% in targeted sectors – steel, coal mining and cement – these cuts would translate to layoffs of up to 3 million workers in the coming 2-3 years. Accordingly, the government plans to allocate $15.4 billion in the next two years to help laid-off workers find new jobs.

Only four decades ago, facing a over-capacity crisis in steel production, the leading industrial nations opted for costly protectionist policies in the steel sector. In contrast, China is eager to sustain globalization and to accelerate world trade and investment, evident in its rolling out of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative and the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS New Development Bank.

Applying the right lessons

What are the lessons of the past crises and new developments described above? Steel crises are multilateral and have global repercussions. Efforts to penalize a single economy are reflective of unilateral and partisan strategies being deployed by crisis-affected economies. Such efforts are part of the problem.

Second, the first steel overcapacity crisis involved major advanced economies, which opted for solutions that harmed world trade and investment and thus global growth prospects. Such policies should be avoided today.

The current steel crisis involves all major economies, even though the leading role belongs to China. As China continues to support and underpin world trade and investment, its role is vital in global growth prospects. Moreover, emerging economies should not be penalized for rapid economic development.

Fourth, Chinese overcapacity can be repurposed towards supporting industrialization and modernization in those emerging economies that participate in initiatives such as the ‘One Belt One Road’ program – advanced economies also stand to gain from this kind of development.

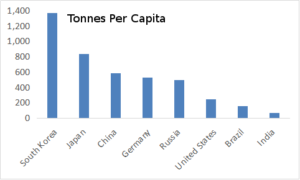

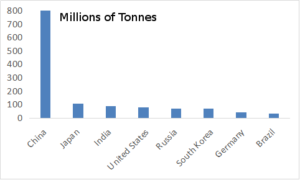

In steel crises, international observers rely on country-aggregated data. However aggregate data should be assessed (a) in terms of the respective country’s level of economic development, because steel demand tends to be more intensive in earlier phases of development, and (b) in per capita terms, because large economies have larger steel demand. In light of these qualifications, the rank of top producers is not led by emerging economies (see Figure 1 below).

Finally, any sustained success in overcoming the second global steel overcapacity crisis must be based on multilateral cooperation between all major steel producers. Together, they will have to reduce overcapacity in the largest aggregate producing countries, while ensuring emerging economies’ retain opportunities and the capacity for rapid economic development in the future.

Figure 1 Top-8 Steel Producers: Aggregate and Per Capita Crude Steel Production, 2015

Source: Data from World Steel Association.

Schreibe einen Kommentar