The German Government had set itself challenging goals for the G20 Summit, developing an ambitious agenda for shaping an interdependent world. The fundamentals of this agenda had already been established when everyone was still expecting Hillary Clinton to succeed Barack Obama as President. But the new White House incumbent is a climate and cooperation sceptic. A man who sets himself up back home against the media, the scientific community and the judiciary, that is, against the entities that keep his power in check. And a man who is divisive on the international stage, favouring protectionism where it serves US interests, withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement and a reduction in contributions to the United Nations. A fickle world power that causes offence rather than working with partners to shape global policy. This is no coincidence.

I have been writing about the G20 for seven years. The G20 has evolved substantially over that time, with an ever-broadening agenda that now covers issues far beyond those envisioned in the first G20 summits in Washington and London over 2008 and 2009, when the G20 was at its peak as a globally influential governance body. As a result, and in order to stay on top of the

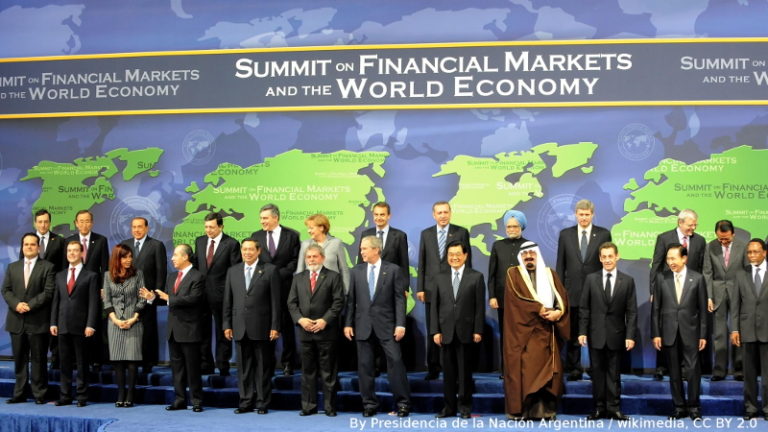

I have been writing about the G20 for seven years. The G20 has evolved substantially over that time, with an ever-broadening agenda that now covers issues far beyond those envisioned in the first G20 summits in Washington and London over 2008 and 2009, when the G20 was at its peak as a globally influential governance body. As a result, and in order to stay on top of the  Two weeks out from the Hamburg Summit, there are plenty of warning signs that this may be the most challenging G20 meeting since G20 leaders first met in Washington in 2008. Then, the global economy stood on the precipice of a dramatic collapse. Staring down the barrel of a long and protracted global economic recession on an unprecedented scale, G20 leaders opted for cooperation via a massive collective global economic stimulus program.

Two weeks out from the Hamburg Summit, there are plenty of warning signs that this may be the most challenging G20 meeting since G20 leaders first met in Washington in 2008. Then, the global economy stood on the precipice of a dramatic collapse. Staring down the barrel of a long and protracted global economic recession on an unprecedented scale, G20 leaders opted for cooperation via a massive collective global economic stimulus program. In a potentially ominous sign for this year’s G20 Summit, pieces from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

In a potentially ominous sign for this year’s G20 Summit, pieces from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung