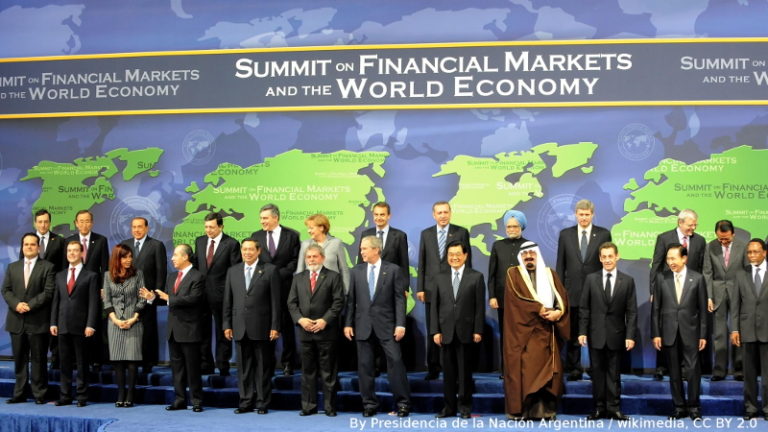

I have been writing about the G20 for seven years. The G20 has evolved substantially over that time, with an ever-broadening agenda that now covers issues far beyond those envisioned in the first G20 summits in Washington and London over 2008 and 2009, when the G20 was at its peak as a globally influential governance body. As a result, and in order to stay on top of the expanded agenda, the trend has been towards greater reliance by G20 Ministers and Leaders upon lower-level officials and bureaucrats to both prepare and even draft the main G20 outcome documents – particularly the final communique.

I have been writing about the G20 for seven years. The G20 has evolved substantially over that time, with an ever-broadening agenda that now covers issues far beyond those envisioned in the first G20 summits in Washington and London over 2008 and 2009, when the G20 was at its peak as a globally influential governance body. As a result, and in order to stay on top of the expanded agenda, the trend has been towards greater reliance by G20 Ministers and Leaders upon lower-level officials and bureaucrats to both prepare and even draft the main G20 outcome documents – particularly the final communique.

As a result, leaders’ discussions in recent years have reportedly drifted towards being more formulaic, with pre-prepared statements being preferred by many leaders to active and dynamic debate. And of the leaders who attended the first few G20 summits, only Angela Merkel and Turkey’s Recep Erdogan are still at the helm of their respective countries, such that the large majority of participating leaders in Hamburg have no first-hand experience of the G20’s role in arresting the 2008-2009 global economic freefall, and the important role host leaders played in those first few meetings in achieving productive outcomes.

For this year’s G20 host, Angela Merkel, this dwindling of institutional memory about the G20’s capacity to allow leaders to make a major impact needs to be addressed. And yet, the maiden appearance of Donald Trump at a G20 leaders’ meeting may just provide the necessary impetus, unwanted or otherwise, to circuit-break the G20’s slide towards predictability.

A robust discussion is better for the G20 than a series of pre-prepared statements

Until now, this year’s G20 presidency has followed a similar path to those of the last few years. A lengthy list of priorities was announced by the German Chancellery last December after taking over the presidency from the previous G20 host China. The priorities were relatively clear, wide in scope, and introduced a few new issues to the G20 agenda, notably in the area of health governance.

However, the task of advancing the various issues listed in the agenda has required a significant amount of input from multiple parties, and not only from officials – by the end of this year, close to one hundred different conferences, workshops and events will have occurred under the auspices of Germany’s G20 presidency. Ten of these events will occur after Hamburg Summit, and somewhere over eighty beforehand. Although many of these pre-summit events were related to one another, such as the four scheduled meetings for finance ministers and central bank governors, they will nevertheless all form part of the background and input that will go into the Hamburg Summit. Even if it is only theoretically how the process works, that is still a lot of documentation and output that leaders will be called to sign off on this coming Friday and Saturday.

But coming together to approve the accumulated output that the G20 ‘industry’ is not meant to be the point of the G20. A mere box-ticking exercise is not worth the time, expense and inconvenience that is required to host a global meeting of this scale. And even if leaders do manage to deliver consensus support for the work of the many G20 policy streams this year, to whom does it really matter that the leaders imprimatur is on the hundreds of pages of documents we can expect to be made publicly available by next week? The communique and supporting documentation from the St Petersburg summit in 2013 came to over 187 pages, and it is difficult to believe that any of the attending leaders that year paid much attention beyond the first few clauses, let alone the entirety of the published outcomes.

Absent an insistence from the host chair to have a robust discussion and tackle the big points of disagreement head-on, the G20 Summits are at risk of joining the large array of international events that simply keep on happening out of habit; what some within the governance community refer to as ‘space junk’ – events that keep on passing by, and that are more complicated to get rid of it than not.

However, when looking for that faint glimmer of light within the many dark clouds that are forming on the horizon of global governance, it seems safe to say that the discussions at this weekend’s summit will at least be robust.

Forget the script – have a debate

For some, the prospect of a heated and robust discussion may be immensely frustrating and undesirable. This may be especially so for those who have spent days, or months even, finely honing and crafting G20 outcome documentation and a potential leaders’ communique that is as minimally offensive as possible. However, as the German G20 Sherpa Lars-Hendrik Roller commented at the recent T20 Summit in May, even if the German chancellery had crafted ‘the most perfect’ agenda and plan for the summit, one capable of solving many of the world’s greatest challenges, it would not matter a jot if it was not capable of winning the support of the other G20 members.

Indeed, how capable this year’s hosts are at pushing through their particular take on the G20 agenda is likely being tested at this very moment, with pre-summit negotiators from G20 countries already drafting and debating the wording of the communique that will be presented to leaders for their approval this weekend. Much of this wording will be simultaneously broad and un-specific in terms of the commitments and obligations on behalf of G20 members, and therefore relatively uncontroversial. There will also be a lot of general agreement on ongoing items in the G20 agenda.

However, the pre-summit salvos from Angela Merkel in the increasingly contentious areas of trade (and fighting protectionism) and climate change, suggest that Hamburg may be somewhat closer to the original G20 summits at least in form, if not in content. How welcome this development is remains to be seen, but the German Chancellor has made it clear that she intends to squarely pursue positive outcomes on trade and climate change that evidently do not accord with the stated views of the Trump administration. In this she has been backed up by the new French President Emanuel Macron, and appears to at least have the rhetorical (if not explicit) support of China. And given the manner in which the US President has approached these contentious areas in the past, the pre-summit negotiators may currently be involved in what is essentially a guessing game about what the leaders will actually conclude in these areas by the end of the Summit.

Under these circumstances, it would not be the worst idea to release two documents: one that addresses ongoing work from previous summits, and one that demonstrates what new directions leaders were able to agree upon specifically at the Hamburg Summit itself (this would also make for a more concise and readable outcome document).

That may not be an ideal place for officials to find themselves this close to the summit – but at the very least, this sort of confusion would be an indication that the G20 is again returning to what it was designed to be: a place for leaders to honestly discuss (or argue even), in person, about what can be done together in the face of the world’s largest challenges. In some ways, a near blank communique that acknowledges an inability by leaders to reach consensus on the big topics would be a refreshing reminder that at least the G20 is still enabling leaders to honestly talk to each other, instead of simply reading off an autocue and rubberstamping bland pronouncements of questionable value. If the G20 has retained its value since 2008, then officials should be second-guessing their leaders, and not the other way around.

Schreibe einen Kommentar