14. The European Union and the United Nations: exploring new opportunities in times of fiscal pressure

Sebastian Haug

in: Hackenesch, C., Keijzer, N., & Koch, S. (Eds., 2024). The European Union’s global role in a changing world: Challenges and opportunities for the new leadership (IDOS Discussion Paper 11/2024). IDOS.

State of play

The United Nations (UN) system is the world’s foremost set of multilateral organisations with quasi-global membership, and the European Union (EU) has long been a staunch supporter of the United Nations. EU support comes through both words and deeds. EU institutions and representatives regularly speak out in favour of strengthening the United Nations as the multilateral core of world politics. In addition, the EU also acts as a coordinator for its 27 member states in UN negotiations, for instance those on General Assembly resolutions. Given the fact that some of the UN system’s most important donors – including Germany, the Netherlands and France (UN-CEB, 2024) – belong to the EU, this coordination function plays a key role in UN negotiations. Compared to most other member states, many EU countries – particularly the larger ones – can count on a substantive workforce in their New York-based missions to prepare and accompany UN debates. This puts the EU in an advantageous position when it comes to co-shaping what are often complex negotiation processes.

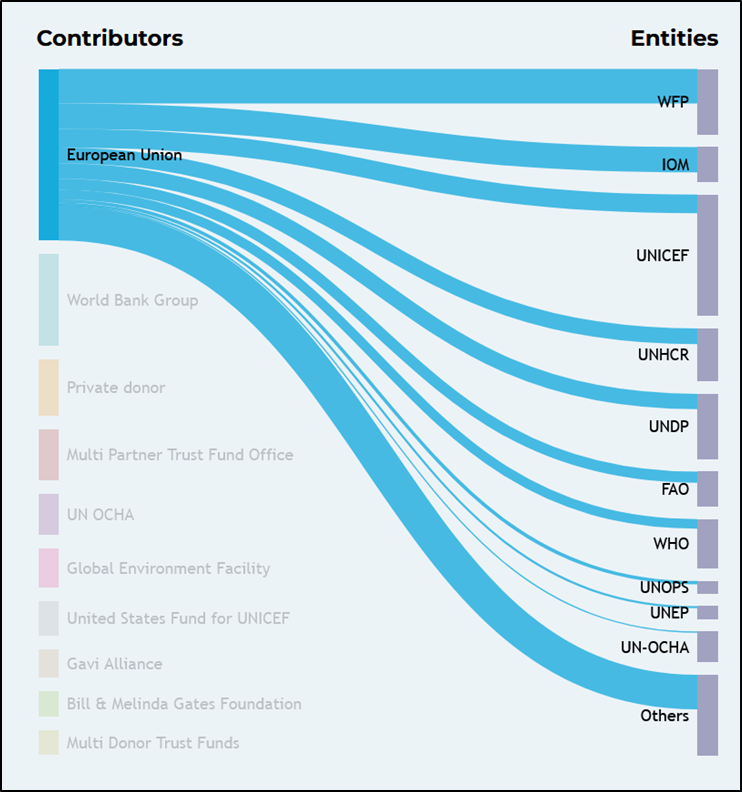

At the same time, and maybe more importantly, the EU acts as the United Nations’s most important “non-governmental” donor (see Figure 1). This is of particular relevance for the UN development pillar, as most UN development entities depend disproportionately on voluntary funding. With a few exceptions, the EU – as a supranational organisation – has no official membership in UN bodies.[1] Contrary to UN member states that also pay membership fees, the EU therefore only provides voluntary funding to UN budgets, most of which is earmarked, that is, dedicated to a pre-specified purpose in line with EU preferences (Baumann & Haug, 2024). The World Food Programme (WFP), for instance, received about USD 700 million from the EU proper in 2022 (the last year for which complete numbers are available). In the case of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), this figure stood at about USD 510 million, covering roughly 20% of the IOM’s total income that year. The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the UN Development Programme (UNDP) also receive sizable amounts from the EU on an annual basis. While EU contributions to the UN system have fluctuated over the last decade, they have seen an overall and substantial increase: from USD 660 million in 2010 to more than USD 3.4 billion in 2022 (UN-CEB, 2024).

Together with its member states, many of which are individually key donors for UN entities, the EU as both an umbrella for its members and an actor in its own right is thus an important backbone of UN work. Without the EU and its member states, a large number of UN entities would either need to reduce their activities or close down altogether. UN entities are aware of this importance and court the EU as a “vital partner” (UNDP, 2024). Similarly, UN programme countries – that self-identify as “developing” and host a UN resident coordinator – see the EU as an important provider of multilateral development work at the domestic level. If the EU were to reduce its UN funding by any significant margin, repercussions would be felt across the UN system.

Figure 1: The European Union as the United Nations’s most important “non-governmental” funder: the distribution of EU contributions to the UN system (USD 3.5 billion in 2022, by individual entity)

Source: UN-CEB (2024), https://unsceb.org/fs-revenue-non-government-donor

Internal and external influences

Although the next five years might see a continuation of established patterns where the EU acts as a trusted supporter and funder of the UN system, mounting challenges might well require adjustments in the EU’s positions and strategies. Increasing levels of geopoliticisation, potential fractures in the “Western” alliance, and domestic contestation stand out as particularly relevant.

Geopolitically, actions by and the relationship with China and Russia are likely to influence EU thinking about its future approach to UN funding. Across the UN system, the rise and fall of UN support for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (Haug, 2024) highlights the extent to which major member state-led infrastructure initiatives – including the EU’s Global Gateway – have a difficult standing in an increasingly geopoliticised context. At the same time, Russia and allies, such as Venezuela and Pakistan, have tried to link UN development discussions in the context of Summit of the Future preparations to debates about unilateral sanctions, problematising how the United States and EU member states have reacted to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine (Gowan, 2024). Indeed, while votes at the UN General Assembly have been strongly in favour of restoring the sovereignty of Ukraine, the sanction regime against Russia has been almost exclusively supported by “Western” states (Simes, 2022). The expansion of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) adds to what many describe as an expanding anti-Western sentiment across world regions. The war in Ukraine and the war in Gaza have brought some of the underlying fault lines to the fore that separate the EU, (some of) its member states, and the “West” more generally from a considerable number of Southern partner countries.

What is more, Trump 2.0 – a potential second Trump presidency in the United States – might well lead the “Western” alliance itself into a(nother) round of internal turmoil (Klingebiel & Baumann, 2024). If Trump is re-elected, the US government is likely to reduce – again – its support for the UN system. This would also affect individual UN entities and raise questions about whether other key donors, including the EU, are ready to step in. With regard to geopoliticisation dynamics in UN fora, it would also point to more far-reaching implications in terms of the EU’s ability and readiness to continue with its multilateral support irrespective of US actions. Insights from the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), for instance, suggest that the effective departure of the United States in 2011 opened the door for China to become a more important player, although less so than one might have expected (Meng, 2024). Should the US government decide to reduce its engagement with UN bodies or withdraw altogether, it is through its financial power and coordination function that the EU could become a key player in shaping the future of the UN system.

Finally, ongoing shifts within the EU domestically come with an additional set of potential challenges. A decrease in support for multilateralism could lead to a general scepticism towards EU funding and support for UN bodies. This could be easily exacerbated by a general and increasing wariness about development-related spending abroad. In a context where right-wing parties have gained ground in key states across the EU – from France, Germany and Italy to Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden – official development assistance (ODA) is (again) strongly under pressure. This is likely to also affect decisions about ODA allocations in the next EU budget cycle (2028-2034). In some ways, multilateral ODA flows are an easier target for budget cuts as they do not directly jeopardise bilateral relations with partner countries. The EU might well find itself in a position where – as a concession to more vocal right-wing party groups and their constituencies at EU and national levels – cutting UN funding looks like a necessary step towards finding new internal balances and cross-party consensus on budgetary questions.

Looking ahead

Against the backdrop of potential challenges stemming from geopoliticisation trends, Trump 2.0 and domestic contestations, what should the EU do to ensure sustainable cooperation at and with the United Nations?

Strengthen and expand coordination strategies: The EU should learn from China’s challenges with the BRI and is well advised to keep the Global Gateway out of potentially complex UN processes to minimise the likelihood of attacks about undue influence. Instead, the EU should support UN structures through established political and financial means. Despite geopolitical preoccupations and sometimes substantive differences in member state outlooks and capacities, it should also make sure that, for internal cohesion purposes, both smaller and larger EU members continue to contribute to and appreciate coordination at the United Nations under the EU umbrella. The EU should also keep an eye on whether and how the expanded BRICS grouping starts using UN processes for joint efforts. Pre-emptively, the EU should strengthen its coordination with IBSA countries – India, Brazil and South Africa – and contribute to reviving the relevance of this acronym to make sure the anti-Western sentiment that often emanates from China-induced and particularly Russia-led efforts does not spread across UN membership.

Prepare the ground for stepping up alliances: The EU should make a conscious and explicit effort to address long-standing grievances and justice claims across the South, also beyond major Southern powers and beyond heated discussions about Ukraine and Gaza. This includes a reckoning with not only rhetorical faux-pas of the past – such as Josep Borell’s allegory of Europe as “the garden” and other parts of the world as “the jungle” – but also the EU’s often self-centred approach to migration and trade questions. The more relations are built and strengthened across traditional divides, and across issue areas, the larger will be the EU’s repertoire for UN-focused alliance-building in the face of geopolitical turmoil or the unpredictability of another Trump-led US government.

Adapt and protect funding flows: Finally, the EU should strategically review the composition of its funding flows to the United Nations and explore the possibility of shifting from earmarked contributions to core funding, where resources are provided to UN entities with no strings attached. A shift to core funding would increase the ability of UN entities to weather funding shortfalls related to a potential Trump presidency, or to balance an increasingly proactive Chinese – earmarked – funding strategy (Haug et al., 2024). In light of the potential criticism from across EU member states about the relevance of multilateral (development) funding, the EU should get ready before critics mount a more concerted challenge. A geopoliticised context requires a strong(er) case for the geopolitical relevance of UN funding in order to underline why supporting the United Nations is in the interest of the EU and its member states. Ongoing global power shifts, the embeddedness of EU economies in global value chains and – last, but not least – the substantial externalities of Europe’s development over the last 200 years provide a wealth of material to craft narratives and arguments that speak to the EU’s various different domestic audiences.

References

Baumann, M.-O., & Haug, S. (2024). Financing the United Nations: Status quo, challenges, and reform options. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) and German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). https://ny.fes.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Financing_the_UN_online.pdf

Gowan, R. (2024). Accommodation available: China, Western powers and the operation of structural power in the UN Security Council. Global Policy, 15(S2), 29-37.

Haug, S. (2024). Mutual legitimation attempts: China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the United Nations. International Affairs, 100(3), 1207-1230. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiae020

Haug, S., Foot, R. & Baumann, M.-O. (2024). Power shifts and international organisations: China at the United Nations. Global Policy 15(S2), 5-17.

Klingebiel, S., & Baumann, M.-O. (2024). Trump 2.0 in einer Zeit globaler Umbrüche? (IDOS Policy Brief 19/2024). IDOS. https://doi.org/10.23661/ipb19.2024

Meng, W. (2024). Is power shifting? China’s evolving engagement with UNESCO. Global Policy 15(S2), 97-109.

Simes. D. (2022). Did sanctions really hurt the Russian economy? Al-Jazeera, 29 August 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/8/29/did-sanctions-really-hurt-the-russian-economy

UN-CEB (United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination). (2024). Financial statistics. https://unsceb.org/financial-statistics

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2024). For the people and the planet. UNDP and the European Union mark 20 years of partnership. https://www.undp.org/european-union

[1] In 2022, the EU provided (very low levels of) assessed contributions to only four UN bodies: the UN Environment Programme, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, and the International Seabed Authority (UN-CEB, 2024).