10. EU energy and climate policy as a balancing act: the European Green Deal among internal and external forces

Alexia Faus Onbargi and Daniele Malerba

in: Hackenesch, C., Keijzer, N., & Koch, S. (Eds., 2024). The European Union’s global role in a changing world: Challenges and opportunities for the new leadership (IDOS Discussion Paper 11/2024). IDOS.

State of play

Climate and energy policy have been two of the European Union (EU)’s top priorities in the last legislature. Despite a turn towards the right at the European Parliament and in several member states and the potential for this surge to complicate EU climate politics, climate and energy are expected to continue to feature centre stage, building on the momentum of the past five years; especially given the fact that Ursula von der Leyen will be President of the European Commission for her second five-year term.

Previously, the European Council posited “building a climate-neutral, green, fair and social Europe” as one of the four main priorities of the EU’s strategic agenda for 2019-2024 (European Council, 2019). Main policies and laws here include the European Green Deal (EGD) (approved in January 2020); the “Fit for 55” package to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% (compared to 1990 levels) by 2030; and the European Climate Law mandating climate neutrality by 2050 (Heidegger, 2024). Equally ambitious policy has surfaced in the domain of energy given the sector’s overwhelming share of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions (75%). For example, in July 2020 the EU’s Green Hydrogen Strategy was approved, aiming to bolster energy security. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the EU launched the REPowerEU Plan to ensure the bloc’s energy security and phase out Russian fossil fuels, notably Russian gas. In March 2023, a new and more ambitious target of reducing final consumption of energy by 38% by 2030 was adopted, for the sake of energy efficiency and savings; in October 2023, the Renewable Energy Directive was revised to increase the EU’s share of renewable energy to a minimum of 42.5% (though aiming for 45%), by 2030.

This domestic attention to climate and energy issues has also translated into important action on the international stage. For example, at COP28 in Dubai, the EU was successful in resisting a final draft text for the Global Stocktake, demanding that clear language around the phasing out fossil fuels was included. Even though the final text was watered down to “transitioning away from fossil fuels”, the EU was praised for “holding the line” against clear resistance to the start of the end of the fossil fuel regime (Koch & Bauer, 2023). In addition, cooperation on climate mitigation has greatly rotated around energy transitions, particularly through Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JET-Ps) with select countries like South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam and Senegal, and bi-lateral green hydrogen partnerships with countries in northern Africa, and the Latin America and Caribbean region.

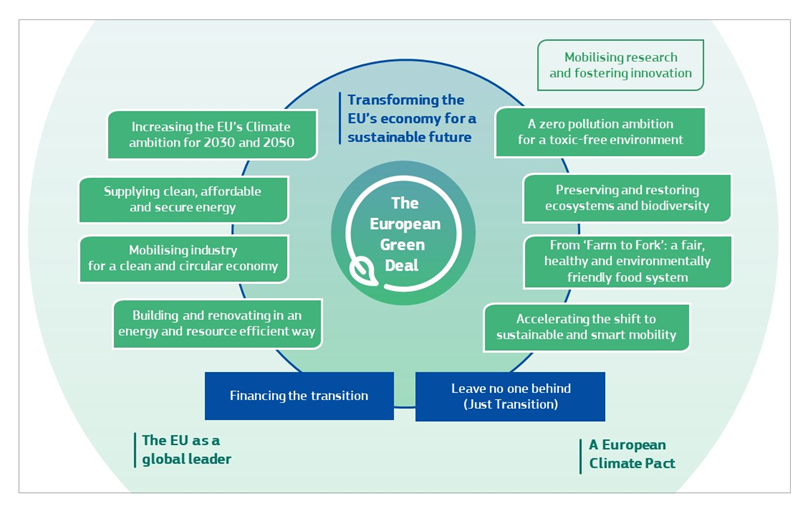

The EGD, shown in Figure 1 below, has nonetheless been criticised for being a largely eco-modernist project that couples ecology and economy to the detriment of social policy, and for being over-reliant on innovative technology that is not available at scale (for example, green hydrogen infrastructure or carbon capture). The EGD is, in fact, still oriented around economic growth. And while it does address the social dimensions of climate mitigation and the energy transition efforts through the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) Fund, these are limited to EU coal-dependent regions.

Figure 1: The European Green Deal presented by the European Commission on 11 December 2019

Internal and external influences

The EGD is a collection of climate- and energy-related legislation focused on the EU and its member states, and designed for the EU to become “the first climate-neutral continent.” However, such domestic policy has implications for policy beyond the bloc. For instance, critics have noted that countries in the so-called Global South are structurally disadvantaged when weathering the impacts of the EGD, able only to react to EGD policies rather than helping to define them according to their own needs and priorities (Claar, 2022).

In addition, the EGD has been criticised for lacking a clear strategy on the extraction of critical raw materials (imperative for electric vehicles, for example), many of which are found in abundance in such countries. Some have warned of the potential for unequal ecological exchange and green colonialism, especially in cases where resources such as water and energy (already insufficient in many developing countries) are poised to produce green hydrogen that would then be exported to the EU.

The EU’s bid for energy security through such partnerships could also put countries in Northern Africa in competition with each other for exports, as well as with countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in addition drive domestic competition (for example, between Spain and Portugal, both of which have great green hydrogen potential). Moreover, the Carbon Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to tax excess carbon imported from beyond the EU is poised to have negative impacts on the economies of various countries of the so-called Global South, especially in Africa.

In terms of the internal factors, one important issue is clearly related to the 2024 European elections. The results of such elections have shown that right and far-right European parties have increased their votes, while the Greens lost significantly. Especially noteworthy was the strong support to far-right parties from French and German electorates, which represent large emitters. While legislation introduced under the EGD is now set in law, the stronger presence of right-wing parties could make ambitious new laws and targets harder to pass. A case in point is the recent proposed goal of reducing GHG emissions by 90% by 2040 compared to 1990 (also mentioned by von der Leyen in her inaugural speech for her second term). In addition, the EGD and climate policies need to strengthen social policy and look carefully at vulnerable groups; for example, the protests of farmers in the first part of 2024 showed that the EGD could be cause for serious backlash and retrenching.

Equally, and if not more important, are external factors that have great potential to shape the EGD and broader EU climate policy. Firstly, the war in Ukraine remains a key challenge. In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion, the EU focused and prioritised fast and secure energy access, for example, through the Aggregate EU platform to coordinate short-term energy supply and access to energy and gas with other countries (European Commission, 2024). Despite still importing Russian gas to this day, the main challenge for the EU is ending one dependency without falling into another in the medium to long term and ensuring it does not support autocratic regimes in its bid for energy security. To replace imports of fossil fuels (coal, gas, and oil) harmful to the climate, EU member states must accelerate and coordinate the development of their own green technologies.

Efforts here are set to be shaped by global renewable energy supply chains and manufacturing. At COP28, the EU was behind the launch of a global target to triple installed capacity of renewable energy by 2030. However, China dominates clean energy supply chains, and the EU has to protect its manufacturers from both Chinese primacy (also made possible by significant subsidies) and US protectionism and tariffs against Chinese measures and products as part of the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Indeed, China’s decisions can significantly affect the EU’s ability to pursue its energy transition and effect European green technology supply chains in the short and medium term. For example, China recently restricted the export of gallium and germanium, metals vital for the making of semiconductor chips; subsequent measures also include export restrictions on graphite, important in battery manufacturing. It also placed a ban on rare earth extraction and separation technologies, in which it is a world leader. Without imports from China of such minerals, green industrial policy in Europe will suffer due to the lack of critical inputs.

Looking ahead

The EU’s 2024-2029 Strategic Agenda highlights the importance of pursuing “a just and fair climate transition with the aim of staying competitive globally and increasing our energy sovereignty” (European Council, 2024). This will require action in several areas.

First, the EU needs to enable domestic acceptability and public support for the EGD if the latter is to survive after 2029 and climate targets are to be met after this legislature. This will require firmly integrating social policy into all EGD-related policies and laws, including around industry, assuring justice and fairness for other groups of society and communities beyond fossil fuel workers, such as farmers, and enabling a Just Transition beyond the energy sector.

Beyond enabling domestic public support for the EGD, integrating social policy into climate and energy policies is also imperative if the EU is to protect its industries from Chinese protectionism and grow its green supply chains in a just and fair manner. Here, the Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age setting out an industrial policy to boost industrial manufacturing of key technologies in the Union, is a good step in the right direction (Scheinert, 2023). The Plan also includes the European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRAMA), which is supposed to address the current dependence on China for critical minerals by increasing the sustainable and resilient production of such minerals in Europe. This Plan would benefit from being more explicitly linked with social policies and social principles, even if social policies are the competence of national governments. The US Inflation Reduction Act, for example, includes strong links with labour policies. In addition, von der Leyen has promised the new “Clean Industrial Deal” in the first 100 days of her second term. There are nonetheless concerns that a greater focus on shoring up the competitiveness of European firms (even if in the context of renewable energy) will water down climate commitments.

Second, there is a strong need to consider global justice in the EGD moving forward – for the sake of both global cooperation and international credibility. For one, the EU must re-evaluate who it partners with to ensure energy imports, foregoing autocratic regimes and focusing efforts on emerging, democratic economies. In addition, there is a need for the EU to better consider and mitigate the potential injustices caused by its focus on securing access to critical raw materials (CRMs) and to green hydrogen in countries in the so-called Global South. The EU must put the principles of equality and equity at the heart of its partnerships; if not, there is a risk of causing resentment and frustration from actors in these states, potentially complicating cooperation on climate and energy.

In addition, and in pursuing climate mitigation and its own energy transition, the EU must also consider energy demand increases in other, poorer, regions. For example, it has been estimated that the energy needs of the African continent are expected to more than double by 2040. There is a risk that Africa’s energy investments will be skewed into producing fossil fuels for European consumption; it is thus critical that the EU also focus on enabling value chains in partner countries. There is also a need to evaluate current JET-P processes and their shortcomings, especially with regard to how finance is channelled and in what format (for example, concessional loans make up the overwhelming majority of such finance).

Finally, the EU must be prepared for the possibility that Donald Trump will be re-elected President of the United States on November 5th. Should that happen, Trump would be widely expected to pull the United States out of the 2015 Paris Agreement for a second time and use his executive authority to weaken climate regulations and expand federal oil and gas programmes so that the EU would need to be prepared for a strained collaboration on climate and sustainability efforts. COP29, which will take place one week after the American elections, will be a crucial moment for the EU to showcase its global leadership in both climate and energy in such a context.

References

Claar, S. (2022). Green colonialism in the European Green Deal: Continuities of dependency and the relationship of forces between Europe and Africa. Culture, Practice & Europeanization, 7(2), 262-274. doi: 10.5771/2566-7742-2022-2-262

European Commission. (2024, 1 February). AggregateEU – one year on (News announcement). European Commission, Directorate-General for Energy. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/news/aggregateeu-one-year-2024-02-01_en

European Council. (2019). A New Strategic Agenda 2019–2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39914/a-new-strategic-agenda-2019-2024.pdf

European Commission. (2019, 11 December). Communication from the Commission. The European Green Deal. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN

European Council. (2024). Strategic Agenda 2024–2029. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/4aldqfl2/2024_557_new-strategic-agenda.pdf

Heidegger, P. (2024). Summary EU Green Deal (EGD) (Böll-Thema 24-1). Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. https://www.boell.de/en/2024/04/29/summary-eu-green-deal-egd

Koch, S., & Bauer, S. (2023). Successfully “holding the line”: The EU and the outcomes of COP28 (Blog). IDOS. https://www.idos-research.de/en/others-publications/article/successfully-holding-the-line-the-eu-and-the-outcomes-of-cop28/

Scheinert, C. (2023). EU’s response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) (Briefing). European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department of Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/740087/IPOL_IDA(2023)740087_EN.pdf

Schreibe einen Kommentar