Introduction

Christine Hackenesch, Niels Keijzer and Svea Koch

in: Hackenesch, C., Keijzer, N., & Koch, S. (Eds., 2024). The European Union’s global role in a changing world: Challenges and opportunities for the new leadership (IDOS Discussion Paper 11/2024). IDOS.

State of play

In response to a host of crises including Covid-19, escalating intra- and inter-state conflicts, a changing climate, the threatening loss of biodiversity, and amidst heated geopolitical competition, the European Union (EU)’s understanding and expectations to its global role underwent significant changes during Ursula von der Leyen’s first term as Commission President. This has brought major changes to key EU policy areas including foreign affairs, migration, trade, climate action as well as its development policy. After two decades of being a self-standing policy area, EU development policy today plays a more facilitating role by being explicitly motivated and positioned to contribute to furthering the “external dimensions” of other EU policy areas including security, trade, energy and migration. The EU’s development policy is expected to promote the EU’s interests and visibility, as well as its strategic autonomy and resilience within the new geopolitical context. It also seeks to support the EU in becoming more autonomous regarding security and defence matters by contributing to diversifying its foreign supply chains.

While it is a commendable step for the EU to better and more strategically integrate the full range of foreign and security, development and economic policies in its engagement with its international partners, it is at the same time a challenging step. Delivering on it hinges on the constant and conscious balancing of the EU’s own geo-economic interests and those of its partners. During the past five years, the EU appears to have prioritised the pursuit of its more assertive and interest-driven development policy in its effort to adapt to a changing global context. Major initiatives such as the Global Gateway and “Team Europe” that were launched under the first von der Leyen Commission have successfully contributed to increasing the EU’s visibility. Global Gateway and “Team Europe” have both in many ways also strengthened cooperation among the EU institutions and member states.

As the policy basis for her second term, Ursula von der Leyen’s political guidelines emphasise the need for Europe to become more assertive in pursuing its strategic interests. One concrete way of doing so is by taking the Global Gateway to the “next level” by developing integrated packages that bring together infrastructure investment, trade policy measures and macro-economic support (von der Leyen, 2024, p. 27). While understandable given the audience and the adage of sticking to the plan, continuing the current direction would carry the risk of fuelling conflicts of interest with a more confident and assertive Global South (see Section 1 on the Global Gateway). Moreover, an overly supply- and interest-driven EU approach to international cooperation may come at the expense of the EU’s flexibility to respond to its partners’ needs and priorities, which would risk eroding ownership and negatively affecting the sustainability of the results that are achieved. The EU’s partners may have observed the complete absence of the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the political guidelines (von der Leyen, 2024); a notable absence in a year when the United Nations is hosting its Summit for the Future to reflect on progress made towards realising this Agenda, and discussing what should happen next (see Sections 15 and 17 in this publication).

Internal and external challenges

Development policy has been much more controversially debated across EU member states as well as at the EU level during the past few years. One important driver of these more controversial debates on the objectives, instruments and budget was the rise of populist radical right parties. During the European Parliament elections in June, the existing pro-European political groups managed to maintain their majority in the European Parliament. Yet, due to their clustering in three political groups, two of which were newly created, the right-wing parties will enjoy stronger access to the EP’s resources and, depending on the level of their fragmentation, also hold a stronger voice in controversial debates. In several key EU member states – notably Italy, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands – populist radical right parties have taken over government responsibility with immediate implications for development policy. Electoral support for the populist far-right is also surging in other major donor countries such as Germany or France.

Populist radical right parties are far from sharing unified positions on development. But they do share a critical view of development aid. They question the relevance of development policy and urge for using development policy to exert a curbing and halting effect on migration flows to Europe. At least partly in response to the pressure by the populist radical right, conservative parties have also taken on more restrictive positions on migration policy in the hope of retaining or winning back voters (for more on the linkage between migration and development policy, see Section 5). Particularly during the negotiation of the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) (that is, the EU’s budget) for the period 2028-2034, populist radical right parties are expected to make their voices heard, while in the process also encouraging other parties to raise theirs. As development assistance budgets are currently being reduced across many EU member states, the next MFF negotiations are likely to become particularly tense with regard to the EU’s external relations budget.

These strongly inward-looking domestic developments in many member states are at odds with the geopolitical situation the EU needs to position itself in, which ultimately necessitates a stronger European engagement in the world. Notwithstanding the important initiatives introduced during the past five years, which are discussed in detail in the various sections of this publication, the EU’s new leadership faces the need to consider larger challenges that concern the EU’s place in the world and its international relations. Both on highly visible and forgotten conflicts (see Section 6 in this publication) but also on fundamental policy directions, the EU and the Global South are currently on different wavelengths. These range from migration, extraction of critical raw materials (CRMs), energy transitions, and the continued extraction of fossil fuels to questions of democracy and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza (See Section 5, 6, 10 and 13 in this publication). Linking EU development policy more explicitly and assertively to the EU’s own strategic interests will fuel, rather than ease, these tensions. In addition, the EU faces the accusation of developing countries that it has failed to consider the external impacts of internal regulations on their economies, most notably those of the EU Green Deal, including the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the deforestation-free value chain and due diligence regulations (see Section 3, 12 and 13 in this publication). In sum, the EU’s continued emphasis on internal priorities has put a strain on its relationship with the Global South.

The EU’s leadership acknowledges the need to listen and respond to the concerns of its partners (von der Leyen, 2024, p. 28). These are welcome signals, yet they will have to lead to concrete measures or tangible changes in policies. The individual sections of this publication present ideas and proposals for reconsidering priorities and directions in various EU policy areas, ranging from climate action, energy, biodiversity and trade to development policy.

2024 and beyond: a need for bold choices and ambition

The political priorities for the next European Commission make clear that Global Europe will focus on Ukraine, enlargement as a geopolitical tool, the Neighbourhood, the EU’s foreign economic policy, as well as multilateralism. The Global Gateway is supposed to be further broadened to foster the EU’s economic interests abroad. While those priorities are certainly key, they fall short in developing a broader narrative as to what the EU wants to achieve in its external relations beyond pursuing its economic and security interests. Notably absent from von der Leyen’s vision for the next European Commission is a perspective on whether, and how, the EU seeks to contribute towards sustainable development globally.

Moving forward, the new EU leadership should consider the following three broader aspects. More specific recommendations are developed across the contributions in this publication.

1) Develop a broader narrative on Global Europe that explains how the EU wants to contribute to global sustainable development: In view of the unsustainable directions this world is taking, the EU needs to develop a new Global Europe narrative that replaces the 2016 EU Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy. This new narrative should lay out how and why global sustainable development is the key focus of the EU’s role and engagement in the world, next to the EU’s own strategic interests. This new sustainability-oriented policy narrative should in turn guide the priorities and directions of other policy areas, including migration, climate and energy, trade and foreign direct investment as well as development. The narrative should also guide the EU’s engagement in upcoming international dialogues, including the upcoming considerations of what new steps and actions are needed towards and beyond the remaining five years under the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals.

The EU’s domestic challenges are deeply interwoven with its global engagement and the EU needs to more carefully weigh in the external dimensions and repercussions of its domestic policymaking on its partners. At the essence, the EU faces the challenge of finding an approach for its global role that reconciles the EU’s strategic and economic interests with the needs of its partners, and that acknowledges and addresses the impacts and spillovers of the EU’s policies on partner countries in the Global South.

2) Refocus and reform the Global Gateway and its relationship with development policy: Not least to live up to the large investment target that was announced for the Global Gateway, the initiative is currently becoming a catch-all framework for various types of economic cooperation with various countries across the Global South (see Section 1). Moving forward, the EU will need to refocus the goals and main components of the Global Gateway to make it attractive and transparent for partners. The rational of the initiative as a “connectivity strategy” is too narrow and too EU-interest-focused for it to fully eclipse and replace the EU’s development policy. On the other hand, aspects of development policy that are not part of the Global Gateway are currently falling off the radar. The EU will thus need to take a two-fold approach: refocus the Global Gateway initiative to make it meaningful and attractive and, in parallel, develop a new and broad political vision for the EU’s development policy.

3) Ensure a strong budget for Global Europe, building on a new narrative for the EU’s contribution to global sustainable development: In light of the multitude of global challenges, the EU will need a strong budget for Global Europe if it wants to remain a relevant global actor. Realising this during the next MFF negotiations will be a challenge given tight budgets across the member states and more polarised debates on the EU’s external action, partly fuelled by populist radical right parties. Building on a new narrative of how the EU wants to contribute towards global sustainable development, the EU institutions and like-minded actors across the EU member states will need to join hands during the preparation and negotiations of the next MFF to ensure a strong budget for Global Europe.

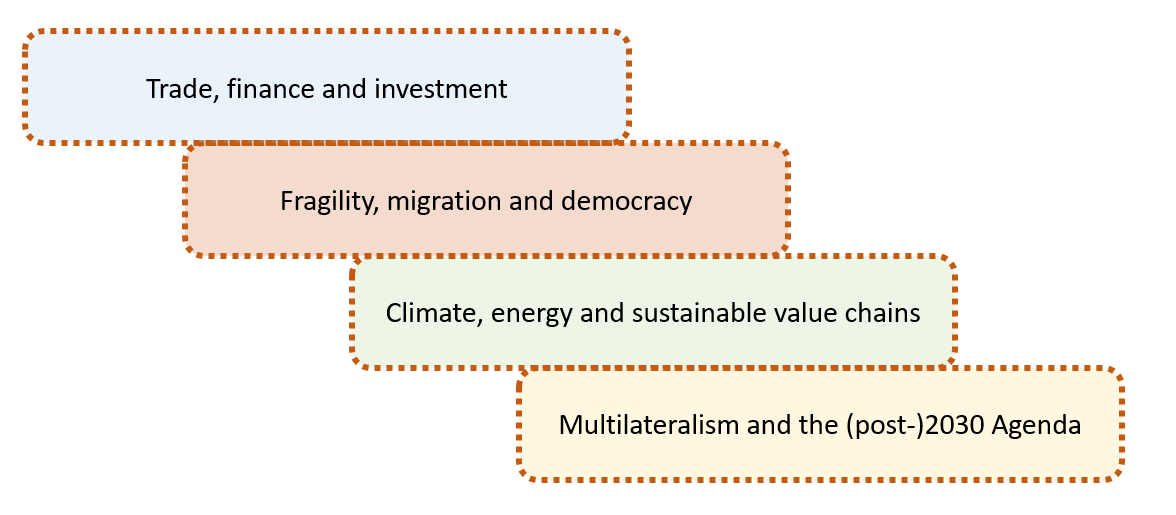

The new EU leadership will need to take bold and ambitious choices to reposition the EU as a leader for global sustainable development in times of systemic and geostrategic rivalry and global polycrises. This publication analyses the status quo, internal and external challenges, and key reform ideas for various policy areas, themes and regions linked to the EU’s global role. The publication’s sections are grouped into four thematic clusters, each representing essential building blocks to strengthen the EU’s global role (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Four clusters for the EU’s global role

Each section addresses three sets of questions and is structured in the same way:

- State of play: Why do we expect this issue to shape EU development policy in the upcoming term, and in which direction? What are the major trade-offs between the EU’s own objectives and partners’ interests, and how has the EU addressed these so far?

- strong>Internal and external influences: How do internal political dynamics in Europe and geopolitical competition affect EU positioning in this area?

- Looking ahead: What needs to be done or changed to secure a stronger focus on cooperation, sustainability and the needs of partners in this area?

References

von der Leyen, U. (2024). Europe’s choice: Political guidelines for the next European Commission: 2024-2029. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6cd4328-673c-4e7a-8683-f63ffb2cf648_en?filename=Political%20Guidelines%202024-2029_EN.pdf

Schreibe einen Kommentar