At the beginning of a new decade, we suggest to look at the longer-term. Let’s consider the world of multilateralism two decade from now, i.e. well beyond the timeline of the 2030 Agenda. The setting in 2040 is likely to differ substantially from today. Things change, and the job of scenario-building is to imagine different futures without merely projecting existing trends or historic examples. Scenario-Building also provides us with ideas about what we need to do to land in the space we see as most preferable.

A joint glimpse at 2040

From today’s perspective, the likely scenario is not rosy: By 2040, the multilateral system is hollow. Joint action at the global level will be organised in ad hoc coalitions, where countries come together on single issues or for short-lived, club-like engagements, most likely not adequately taking care of the interest of the most vulnerable. In a world that is heading towards an average temperature that is three degrees Celsius warmer than during pre-industrial times, vibrant coastal regions of today will be inundated or suffer from flooding and storms, other regions will become too hot for human settlements, and droughts will increasingly threaten harvests, with local, regional and global impacts. Some forms of more inclusive cooperation and an orientation towards global commons might be forced upon the system because of acute pressures from unresolved global problems. Yet more powerful actors might rather look after their own short-term national interests. In this world, multilateral cooperation – that is, inclusive, rules-based cooperation that allows a distribution of benefits over time and in the aggregate for all participants – is clearly the exception, not the norm.

This bleak assessment came out as one possible future in a scenario-building exercise by researchers from Europe and a number of large countries from the global South, namely China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa, as well as experts from international organisations. The task was to think about the future of multilateralism which we understood as intergovernmental cooperation – distinct from unilateral action but also other forms of cooperation where private actors place a larger role. The group came together for a conference organised by the German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) and the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation at the end of 2019, and also included experts with civil society and private sector background.

Whither multilateralism?

Scenarios will never predict the future. Indeed, the whole exercise is about futures in plural. Rather, they offer different perspectives and allow for a discussion of drivers that push or pull us into different directions. Through telling different stories about what the future could look like, scenario-building allows for a broader perspective on where the world might be 20 years down the line. We deliberately invited to think about multilateralism in 2040, i.e. considerably after 2030 as a target year for the 2030 Agenda.

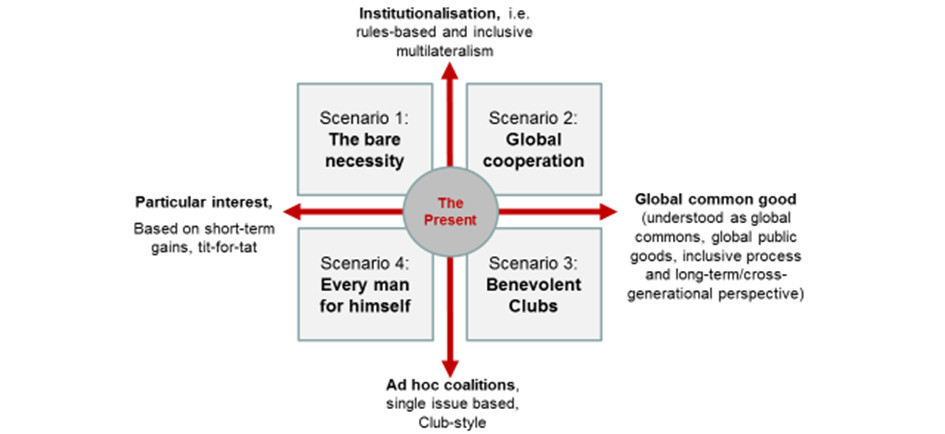

Diagram 1: Deriving at scenarios for the future of multilateralism

Diagram 1: Deriving at scenarios for the future of multilateralism

Discussing multilateralism, we established two axis along which we assume our current system will change: one designates the spectrum from a highly institutionalised, inclusive cooperation that is also based on binding rules and where impartial international organisations play important roles to an ad hoc cooperation, addressing specific issues and in a selective club format. The second axis ranges from a world in which states and other actors operate on short-term self-interests to a world that orients itself at what we called the global common good. A global common good orientation encompasses three elements: a) global commons are protected and global public goods provided, b) inclusive procedures ensure that all affected have a say, and c) the interests of future generations are taken into account. (To date, the best real world embodiment of such global common good orientation is probably the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.)

Using the two continuums, the group arrived at four scenarios:

- The bare necessity of very “thin” multilateralism (states still accept norms such as sovereignty and some forms of international law but otherwise are not overly willing to bear the costs of multilateral cooperation)

- Global cooperation with thick, inclusive multilateralism (binding rules, strong organisations, networked institutions that are able to deal with complex, cross-cutting issues), directed not only towards the lowest common denominator but geared towards addressing global problems and the interests of future generations.

- Benevolent clubs, with cooperation aiming at providing global common goods and fostering sustainability, yet suffering from inclusiveness and possibly reach.

- Every man for himself in a rivalry amongst states and powerful non-state actors about short-term interests and survival.

Key drivers that affect the direction of the future

The group of researchers and practitioners identified four major forces that are likely to shake and move the world for the next twenty years: climate change, power shifts, technology and inequalities. Besides those drivers, factors such as demographic growth and change, are highly predictable and will have substantial impact. In all scenarios, we assumed a world with 9 billion people, in which Africa alone will be home to 2 billion people (and thus double from current figures).

Driver no 1: climate change.

The most powerful driver, the group agreed, will be climate change. A world of three degrees warming over pre-industrial times – and most saw this as a distinct possibility – would look massively different from today: Coast lines would reshape, with cities such as Shanghai, Lagos or Bangladesh as a country being below sea level. Whole regions might also become too hot for human settlements. Such inundations would result in massive migration in and across African and Asian countries, also affecting Europe and North America. New York, for instance, was discussed as below sea level, never mind New Orleans or most of the Netherlands. Food production would be severely affected by extreme weather events and changing rainfall patterns across the globe. In the „best case“, the effects and threats of climate change would increase the challenges to a degree that leaders and societies understand the need to cooperate in a structured way so as to tackle the challenges together, moving to govern resources justly and sustainably (Scenario Global Cooperation). Climate change might, however, as well result in a „every man for himself“ scenario, where states close borders and retract to the mere necessity of joint self-defense, rather than shaping a global common good proactively, with a view to solidarity and an understanding of a common future.

Power shifts change international dynamics drastically

In 2040, China will have further established itself as a major power, alongside other large powers, such as the US, India and the European Union. There will be no single hegemon that willingly invests in multilateral cooperation and guarantees its attractiveness for others, including a more populous African continent. This will make the world politically more volatile – or flexible, depending on viewpoint. Changing between different forums (forum shopping) is more likely, as powers will seek to circumvent institutions that block their immediate interests. The Club scenario speaks more for a proliferation of smaller coalitions of interest, be that in setting like the G20, BRICS or G7, or – more likely – in thematically even narrower settings. Yet it is also conceivable that some of the great powers (re)discover the United Nations, which might allow for its reform and strengthen multilateralism that is more about diffuse gains, not immediate tit-for-tat politics.

Technology: new opportunities – yet no magic wand

Technology increases interactions and could turn into a game changer. Compiling and mining large quantity of data (including through the internet of things) will be a key element for success, both for states and private actors. Technological change could increase productivity and might mean a more humane work environment if the shrinking demand for human workforce is evenly translated into gains in leisure time. Alternatively, it could lead to larger parts of population without work. Technology could also allow for more targeted actions, potentially supporting the sustainable use of resources, or new forms of citizen participation, and innovation can provide new solutions we do not see yet (so-called „black swans“). However, risks are high, too: In any case, technology will drive a higher demand for energy. Our dependence on technologies also turns key infrastructure, such as electricity grids, transportation or water supply, into vulnerable target in conflicts. Proliferation of advanced military and information technologies increase the risks of cyber-crimes and weapons based on artificial intelligence that may or may not be under the control of governments. Non-state actors gain ground, too, not least so companies that build on technology and, more importantly: data. Should markets remain largely unregulated and tech companies expand their monopolies and build oligopolies, the risks of conflict rises. Data, the most important resource, becomes property of giant private companies, creating tensions in societies who demand action from their (weakened) states.

Crises of capitalism and rising inequality

Inequalities within states might lead to stronger polarisations and unrest, further nurturing the perception of systemic crises on which populist movements feed. This could force states to become more inward-looking and defensive, if not aggressively seeking advantages beyond their border, e. g. by exploiting data control or by forcing attention by acting as international spoiler. It could also further decrease governments’ ability to act faced with global problems. Yet it seems possible that in a scenario of global cooperation, states would jointly regulate non-state actors and include them in solutions for the global common good, possibly with a Tobin tax on financial transactions. In a club scenario, states would at least work together, not least so further pushed by a likely next financial crisis.

Conclusions

As 2020 begins, it is a good moment to reflect on where we stand and where we are heading. Worryingly, agreement was in the group that, by 2040, we are likely to live in world heading towards an average temperature increases of three degrees in which a number of ecosystems have surpassed tipping points. Furthermore, data – and control of data – was consensually seen as crucial for all drivers.

No agreement was reached, though, when we turned the question from ‘the most likely’ to ‘the most desirable’ scenario. While all agreed on the (broad) idea of working towards the global common good, not all discussants wanted an institutionalised world of ‘thick multilateralism’. The club scenario, based on a re-gaining of national sovereignty, was also seen as a good option by some. This probably reflects the composition of the group, in which all participants came from states with substantial power resources.

Scenarios are meant to prepare for possible futures. While we cannot and do not want to predict what the world will be like in 20 years, nevertheless two lessons emerge from this exercise for European decision-makers: they will need to pragmatically cooperate with actors that are not amongst the like-minded in their outlook on the world, but are necessary partners to address urgent global issues. The pressure for global problem solving might catalyse cooperation amongst unlikely partners. Yet at the same time, European decision-makers should not refrain from stressing the importance and benefits of more inclusive and principled ways of multilateral cooperation, also reflecting on the fact that Europe has disproportionally been benefiting from the multilateral system as it exists today.

Schreibe einen Kommentar